About Mexico

Mexican Traditions and Culture

The words of the Mexican textbook, Mi libro de Historia de México: Quinto grado, also describe the unique, rich cultural heritage: “ The Mexicans of today inherit a vast culture that is thousands of years old. It began with the great ancient civilizations ... In the continuity and richness of our culture is the greatest part of the secret and strength of our national consciousness” (SEP p.154).

Mexicans share the legacy of both Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe. In the words of Octavio Paz:

In the Valley of Mexico man feels himself suspended between heaven and earth, and he oscillates between contrary powers and forces, and petrified eyes.... Reality...that is...the world that surrounds us...exists by itself here, has a life of its own, and was not invented by man as it was in the United States (p. 20).

Michael Parfit also discusses the Mexican duality:

... for most Mexicans the deepest ties to this land date not from the arrival of a ship loaded with homesick Europeans but from people who came here on foot so long ago that even myth does not remember. Within the blood of these Mexicans run the civilizations of Olmec and Maya and Aztec, as well as the urgent hungers of the Spanish (p. 16) This makes for a rich culture. The Roman Catholic Church dominates spiritual life, but in Mexico its rituals, like the candles and candy skulls of the Day of the Dead, are so imbued with indigenous tradition that you can almost hear the wail of an Aztec war song in the smoky shadows of village churches (p. 17).

The tumultuous landscape, history, and complex psyche have served as fountains of creativity. The heritage includes an impressive tradition in the fine and folk arts. Mexican artisans produce a dazzling array of items from silver, gold, tin, leather, cloth, clay, wood, stone, and glass. A long list of great writers includes Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes, Juan Rulfo, Mariano Azuela, Agustín Yáñez, Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera, and many more.

A by-product of the Mexican Revolution has been the work of the twentieth century world-renowned artists Orozco, Rivera, Siquieros, O’Gormon, and Tamayo, whose mosaics and murals often express political themes. The music is quite varied, from the compositions of Carlos Chávez to the mariachi of Jalisco, the polkas and ranchero music of the North, or the marimbas of Veracruz and mucho, mucho más. Mexican creativity also expresses itself in a thriving film industry. Mexican cuisine is considered one of the five best in the world.

“La Educadora” by Miguel Miramontes Escuela Normal de Jalisco

Hispanic Heritage

Spanish exploration of what is now the United States began in the early 1500’s and continued until the 1700’s. The exploits of early explorers like de Soto, Ponce de León, Narváez, and Cabrillo as well as the subsequent establishment of missions in Texas and California are well known. Florida school children learn about the Spanish exploration and colonization of their state and visit the oldest city in the United States, St. Augustine.

Perhaps less well known is the key role Spain and the Spanish colonies played in the American Revolution and in our Civil War. During the Revolution, Spain provided money, guns, and supplies to the colonists. The Spanish governor of Louisiana sent food, medicine, and guns. Other Spanish colonies sent soldiers. In Cuba, rich women even gave away jewelry to help the war effort. Almost 10,000 Hispanics fought in the Civil War, some for the Union and others for the Confederacy.

As Spanish, then Mexican lands were appropriated by the United States beginning in 1803, Hispanic influence remained. It can be seen today in thousands of Spanish place names, large populations of Hispanic Americans, food, music, architecture, and customs. Five hundred years of Hispanic Heritage have created and defined many facets of contemporary United States culture.

Food and Language

Nowhere is the integration of American and European cultures so evident as in our diet. The Spanish brought to the Americas wheat, rice, lemons, grapes, oranges, pomegranates, and sugar cane. They also introduced sheep, cows, and chickens.

Indians of the Americas cultivated many fruits and vegetables that were unknown in Europe at the time of the Conquest in the early 1500’s. Some of the more important foods that Mexico shared with the world are chocolate, tomatoes, corn, vanilla, squash, peanuts, chiles, pinto beans, yams, pineapples, papayas, and the maguey. From the animal world, Mexico contributed the turkey.

The words chocolate, tomato, and avocado, are derived from the Nahuatl (Aztec) words chocolatl, tomatl, and ahuatl.

Spanish has contributed more words to American English than any other language. Among these are: the names of seven states; foods such as cocoa, tuna, and barbecue; vehicles named Aztec, Fiesta, and Camaro; place names by the thousands; animal names like iguana, alligator, coyote, and mosquito; and many more, such as plaza, poncho, canyon, patio, and tobacco.

Holidays and Celebrations

¡Viva la Independencia!

September 16

The turmoil created by the French invasion of Spain prompted a group of New Spain’s (Mexico’s) political and church leaders to organize an insurrection against their colonial masters. Captain Ignacio Allende, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, and others intended to declare Mexican independence in December, 1810. The plot was betrayed. On September 15, 1810, Father Hidalgo decided to call the people to arms. Sometime during the night of September 15, or the early morning hours of September 16, he began to ring the bell of his parish church in the town of Dolores. As people gathered, he raised the first Grito de Dolores, shouting, “¡Viva México! ¡Viva la Independencia!” Hidalgo was captured, shot, and his head put on display less than a year later. Mexico did not achieve independence from Spain until 1821.

Photograph of the mural “Miguel Hidalgo” (1949) by José Clemente Orozco in the Guadalajara town hall.

Photograph of the mural “Miguel Hidalgo” (1949) by José Clemente Orozco in the Guadalajara town hall.

Today, Mexico celebrates its independence on the 16th of September. On the evening of September 15, the president of Mexico repeats the Grito de Dolores from the National Palace in Mexico City, replicating Father Hidalgo’s cry for independence. In every village in Mexico, the Grito is given simultaneously by the mayor. In many areas of the United States there are local festivities sponsored by the Mexican Consulate

El Día de La Raza

October 12

Some celebrate the arrival of Columbus 500 years ago. But for others October 12 signifies the subjugation and enslavement of the indigenous civilizations of the Americas.

Everyone agrees that five centuries ago two disparate races confronted each other in a brutal cultural encounter. In Mexico, October 12 is not called Columbus Day but rather El Día de La Raza or “The Day of the Race,” because the intermarriage of Spaniard and Indian created a new race.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to explore extensively, conquer, and colonize most of the Americas and the Caribbean. Hispanic influence is evident in our geography, history, arts, sciences, language, food, music-almost every aspect of contemporary life in the United States. Five Hundred Years of Hispanic Heritage were celebrated in 1992 throughout the United States as part of National Hispanic Heritage Month.

Día de Los Muertos

November 2

November 1st and 2nd are important days in Mexico. The first is All Saints’ Day and the following, All Souls’ Day, is celebrated as the Day of the Dead (el Día de los Muertos).

Traditional baked goods from el Día de los Muertos

The Día de los Muertos is a mixture of indigenous beliefs and Roman Catholicism. On this special day, families attend mass then clean and decorate the tombs of their loved ones with flowers and candles to celebrate the return of their spirits.

Image of celebration of el Día de los Muertos

In their homes, Mexican families arrange altars that usually include a picture of the deceased along with special flowers called ampazúchil, and paper cut into designs. The family may flank the altar with various items that may have belonged to the dead person, such as a hat or machete for the men, a rebozo (a Mexican shawl) or molcajete (utensil for grinding chiles) for the women, and toys for children. The altar traditionally includes food the deceased enjoyed during his or her life plus traditional dishes such as mole, tamales, pan de muerto (bread of the dead), fruit, candies, and drinks such as chocolate or tequila.

There are toys made especially for the Día de los Muertos, such as paper maché masks or coffins with a skeleton that jumps out. Other customs include presentations of the play “Don Juan Tenorio” and school children’s compositions of satirical, rhyming poems called “calaveras.”

In the National Geographic video, The Mexicans, Through Their Eyes, the late Rufino Tamayo explains the Mexican attitude toward death. According to Tamayo, the Mexican character is unique, in part because of the juxtaposition of tragedy and comedy. “We’re tragic on one side,” he comments, and... at the same time we have a sense of humor, and we make fun of the tragedy.” As an example, Tamayo points to the eating of sugar skulls on the Día de los Muertos.

The same video contains powerful visual images and a rich verbal description of the Día de los Muertos. It describes the importance of the celebration by explaining that “...death in Mexico also carries the mystique of another heritage, but it is unique in Mexico in that it joins pre-Columbian beliefs to proclaim that in death there is no end.”

Nobel laureate Octavio Paz devotes an entire chapter to the Día de los Muertos in his treatise on Mexican character, The Labyrinth of Solitude. He discusses the Aztec and Christian attitudes toward death by describing it as “transcendence” (p. 56).

Paz also discusses the importance of fiestas in general:

The solitary Mexican loves fiestas and public gatherings. Any occasion for getting together will serve, any pretext to stop the flow of time and commemorate men and events with festivals and ceremonies...There are few places in the world where it is possible to take part in a spectacle like our great religious fiestas with their violent primary colors, their bizarre costumes and dances, their fireworks and ceremonies, and their inexhaustible welter of surprises... There are certain days when the whole country, from the most remote villages to the largest cities, prays, shouts, feasts, gets drunk, and kills in honor of the Virgin of Guadalupe or Benito Juárez (p. 47).

In addition to the fiestas provided by the Church and the State, every village and city celebrates its patron saint. According to Paz, the frequency and lavishness of the Mexican fiestas serve as a measure of their poverty. “Fiestas,” he explains, “are our only luxury” (p. 49).

The Mexican Revolution

November 20

November 20 commemorates the beginning of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. This long and bloody struggle ended the dictatorial regime of General Porfirio Díaz and provided the framework for many laws and reforms that changed Mexican social and political structures.

Photograph of the mural “Sufragio efectivo,

Photograph of the mural “Sufragio efectivo,

no reelección" (1968) by Juan O'Gorman in the Museum

of National History, Mexico City

During the 30-year Díaz dictatorship, the construction of mines, railroads, and factories created a false appearance of prosperity. In reality, only a small, elite ruling class, many of whom were foreigners, benefited from the political, economic, and social inequalities that characterized Mexican society. The majority labored in poverty. Citizens were not allowed to vote.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, Francisco Madero, a wealthy landowner, led a new generation of leaders in a political campaign against Díaz. Madero was arrested and jailed but managed to escape and take refuge in the United States.

From San Antonio, Texas, he published the “Plan de San Luis Potosí,” calling for a revolt to begin on September 20, 1910. The revolt failed but served to rally support for Madero. He returned to Mexico to lead an armed insurgence, which was joined by Francisco “Pancho” Villa in the north and Emiliano Zapata in the south.

In 1911 the revolutionary forces defeated Díaz. The rallying cry of “Effective suffrage, no re-election,” (Sufragio efectivo-no reelección) became a reality when Madero was elected president.

Madero’s regime was short-lived. He was executed in 1913 by Victoriano Huerta, who was in turn opposed by Emiliano Zapata, Alvaro Obregón, and Venustiano Carranza. Years of bloody anarchy followed.

Eventually, Venustiano Carranza assumed the presidency and presided over the promulgation of the Mexican Constitution of 1917, which is still in effect. This Constitution and the reforms that followed mandated land distribution from the wealthy landowners to the peasants, limited the power and confiscated the property of the Roman Catholic Church, guaranteed universal suffrage, and provided for the formation of political parties.

The Mexican Revolution provided the backdrop for heroes of legendary fame whose deeds are celebrated in great works of art as well as in ballads called corridos. Public school ceremonies commemorating the Revolution often include plays and songs describing the events.

Christmas in Mexico

Photograph of the mural "La Piñata" (1943) by Diego Rivera at the Children's Hospital in Mexico City

There are very few places in the world where Christmas is celebrated so thoroughly and with so much color as in Mexico. Observances are festive and combine religious and social traditions. Two of the most typical traditions are the Flor de Nochebuena, which the United States borrowed, and the Posadas.

The United States borrowed the “Christmas Eve Flower” from Mexico when Joel Poinsette, U.S. ambassador to Mexico, brought the plant back to his native South Carolina in 1829. There are several beautiful legends told about the Flor de Nochebuena, all involving a child too poor to offer a gift to the baby Jesus at the local church. The poinsettia, with its flaming leaves, appears miraculously.

This celebration begins on the night of December 16 and continues for nine nights, through Christmas Eve. Posada means inn; the Posadas commemorate the journey of the Holy Family in the story of the Nativity.

Families visit nine homes each night. They form a procession carrying lighted candles, and are led by two children who represent Mary and Joseph. At the door to each house they stop and beg admittance but are refused until they arrive at the appointed house. At the designated house, prayers are followed by a party during which the children break the piñata.

Birthdate of Benito Juárez

March 21

The 21st of March is the only date on the Mexican school calendar that commemorates the birth of a national hero. Don Benito Juárez was born on this date in 1806 in the village of San Pablo Guelatao in the state of Oaxaca. His parents, who were Zapotec Indians, died when he was three years old.

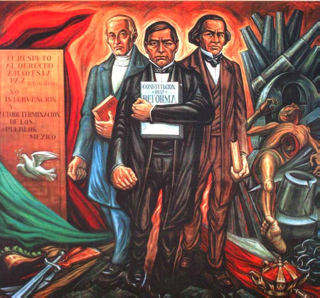

Photograph of the mural “La reforma y la constitución” by Guillermo Chávez Vega (1964) in the Guadalajara Palace of Justice

Photograph of the mural “La reforma y la constitución” by Guillermo Chávez Vega (1964) in the Guadalajara Palace of Justice

Benito Juárez neither spoke nor wrote Spanish when he moved to the city of Oaxaca at 13 years old. He was educated by Franciscans at the Santa Cruz seminary and later graduated with a law degree from the Institute of Arts and Sciences. He became a judge and from 1847 to1852 served as governor of the State of Oaxaca.

The federal government of Santa Anna exiled Juárez in 1853 because of his support for the liberal movement, which sought constitutional reforms. In 1855 he returned to Mexico, became Minister of Justice, and enacted a law called the Ley Juárez, which limited the power of the Roman Catholic Church. Juárez led the liberals in a civil war against political conservatives and Roman Catholic clergy. He was elected president of Mexico in 1861.

Benito Juárez led the struggle against the French occupation of Mexico from 1862-1867. He separated the powers of church and state, fought for land reform, and limited the powers of the military. Benito Juárez died in 1872 during his second term as president.

Don Benito Juárez has served as role model for generations of Mexicans because of his unbreakable will, love for liberty and social justice, and personification of the most noble of ideals. He was named “Benemérito de las Américas” (Hero of the Americas). He is probably best remembered for his declaration, “Among individuals as among nations, respect for the other’s rights is peace."

Cinco de Mayo

5th of May

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) caused Mexico to lose more than one half of its territory and provoked a severe economic crisis. President Benito Juárez suspended debt repayments to England, Spain, and France. The English and Spanish accepted the terms, but Napoleon III of France sent troops to force repayment.

At the time of the Battle of the Cinco de Mayo, the French army was thought to be the premier army in the world. Mexican General Ignacio Zaragoza commanded a much smaller force of ill-equipped soldiers, some armed only with machetes.

One year after the defeat at Puebla, the French sent reinforcements, took control of Mexico City, and installed Maximilian of Hapsburg as the reigning monarch of Mexico. In 1867, Benito Juárez regained power when troops under his command retook Mexico City and executed Maximilian.

Even though the subsequent French conquest and control of Mexico diminished the significance of the Cinco de Mayo, the victory of the Mexicans was symbolically important. It provided a rallying cry and a source of nationalistic pride that reverberates today in the celebrations in Mexico and in the United States.

Photograph of the painting "Juárez, símbolo de la república contra la intervención francesa," (1972) by Antonio Gonzáles Orozco

Photograph of the painting "Juárez, símbolo de la república contra la intervención francesa," (1972) by Antonio Gonzáles Orozco

You can read more about Cinco de Mayo.

Mother's Day

May 10

The celebration of Mother’s day in Mexico dates from 1922 when the daily newspaper Excelsior proclaimed a special day to honor mothers. It is a day when families, businesses, and schools join in expressions of love and respect. Mother’s Day is not marked as a holiday on the Mexican school calendar, but it is a very special activity in all primary and secondary schools. The observance may be as simple as a bouquet of flowers or as elaborate as a grand festival. In some schools teachers coordinate dramatical presentations, recitation of poems, and typical dances performed by the students. These events often involve elaborate sets and costumes. The honored guests sometimes participate in games, and often the students and teachers will prepare typical food for the mothers.

Teacher's Day

May 15

The tradition of Teacher’s Day originated in the city of San Luis Potosí, where a group of young people met every 15th of May to honor their most beloved teacher. In 1917 President Venustiano Carranza signed into law the observance of Teacher’s Day.

On May 15, students, parents, and the community recognize teachers with a festival that includes dances, recitation of poems, flowers, food, and presents. The federal and state governments join the National Teachers’ Union in awarding bonuses to teachers who have completed 30 or 40 years of service.