Education in Mexico

Overview

Since the Revolution of 1910, education has been a priority of the Mexican federal government. In the years since the founding of the Ministry of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP) in 1921, the average schooling has increased from completion of one grade level to more than 7.7 years of schooling, and the illiteracy index has been lowered from 68 percent to less than 10 percent (Perfil de la Educación en México p. 5).

This has occurred despite significant growth of the school-age population. In his recent study of Mexican public schools in Jalisco, Christopher J. Martin refers to Mexican public education as one of the indisputable achievements of the Mexican Revolution (p. 81).

If the Revolution established education as a national priority in 1921, the National Accord for the Modernization of Basic Education (Acuerdo Nacional para la Modernización de la Educación Básica) of 1992 reaffirmed the government's commitment to effect sweeping reform.

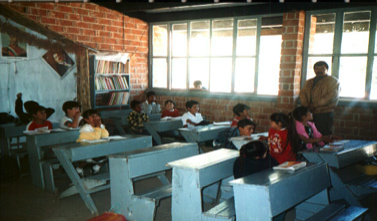

Students and parents gather at a school meeting in Jalisco.

Students and parents gather at a school meeting in Jalisco.

The Agreement was signed by federal authorities, the governors of the 31 states, and representatives of the National Teachers' Union (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, S.N.T.E.). Few aspects of Basic Education (preschool, elementary, middle school, and teacher training, called normal) were unaffected.

This Accord, in conjunction with the Third Article of the Mexican Constitution (Artículo 3∘ Constitucional), the General Educational Law (Ley General de Educación), and the National Education Program 2001-2006 (Programa Nacional de Educación 2001-2006) forms the legal and operative basis for a national educational system that is free, secular, and obligatory. It addressed three general areas:

- Reorganization of the educational system

- Reformulation of educational content and materials

- Reassessment of the educator's function

In terms of reorganization, decentralization was the focus. In 1992 the responsibility for Basic Education was transferred from Mexico City to the states, which disperse funds, provide services, and employ personnel. State authorities also exercise limited choices in curricular content. The federal government, through the Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP), retained control over the following:

- Formulating national plans and programs of study for Basic and Normal Education

- Writing and disseminating the national school calendar for all levels of Basic and Normal Education

- Publishing and updating free, nationally distributed textbooks

- Writing and editing teachers' guides

- Regulating a national system of credits

- Establishing procedures for evaluating the national educational system

- Providing extra resources to states with the greatest needs

- Establishing norms governing the operation of private schools

- Implementing educational programs for adults

- Providing special support services in the form of federal programs for the most vulnerable groups, including migratory, handicapped, and indigenous children, as well as those who live in rural areas

The third area of reform addressed plans and programs of studies, as well as instructional materials. The focus became the development and application of basic communication and computational skills, acquisition of knowledge to help children understand and interact with social and natural phenomena, development of community values, physical exercise, and fostering appreciation for the arts. Instruction became more child-centered with greater integration of subject areas.

Instructional materials returned to an emphasis on Mexican history and the development of national identity. In addition to teaching children about their local area and region, they promote pride and respect, especially for the numerous ethnic groups, their customs, and languages.The new curricula also reflected an effort to achieve greater continuity of studies, particularly between the primary and secondary levels. The new national textbooks for the primary grades represented the first major revision in 20 years. Instructional materials returned to an emphasis on Mexican history and the development of national identity. In addition to teaching children about their local area and region, they promote pride and respect, especially for the numerous ethnic groups, their customs, and languages.

To compensate for the lack of libraries in some schools, the government developed and published "Reading Corners" (Rincones de Lectura) for primary schools. These are collections of high-quality, supplementary books arranged by grade level. In conjunction with an initiative called the National Reading Program (Programa Nacional de Lectura) the SEP has extended the Rincones de Lectura to pre-school and secondary schools. To request a free collection of these books, just contact your local consulate.

Because teachers in Mexico have been called "protagonists for excellence," the "re-assessment" of their role seeks to provide professional development, basic salary increases, and career ladder incentives. In the first year, almost 450,000 teachers signed up for the career ladder.

During school term 1996-1997, the SEP began the first phase of the National Program of Continuous Staff Development for Practicing Basic Education Teachers (Programa Nacional para la Actualización Permanente de los Maestros de Educación Básica en Servicio, ProNAP). The government offers free in-service classes at teacher centers in every state.

Another significant change was the extension of obligatory education, which had included only the six years of primary school. Beginning school term 1993-1994, completion of secondary school (the equivalent of grades seven, eight, and nine in the United States) became mandatory.

The Accord also promoted more social participation involving the municipalities, states, and entire community in educational management and improvement. One approach to improving community participation has been through the creation of Councils of Social Participation in Education (Consejos de Participación Social en la Educación). School personnel, students, former students, parents, businessmen, and politicians participate.

Acccomplishments, Challenges and Goals

The Mexican educational system has achieved significant progress by expanding coverage and improving quality. The number of students increased from 11.5 million in 1970 to more than 30 million in 2001 (Programa Nacional de Educación, 2001-2006, p. 58). Because of the population distribution, one-third of the population was enrolled in formal schooling in 2000 (Programa Nacional de Educación, 2001-2006, p. 68). Public expenditure on education as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product as well as in real terms has increased significantly, reaching more than 6 percent in 2001.

The Mexican school system has responded to high rates of illiteracy, high birth rates, population dispersion, geographical and linguistic obstacles, as well as regional differences in income and productivity. In its effort to universalize public education, the government has constructed and staffed thousands of public schools, including one-room schoolhouses, established satellite-delivered secondary level classes (Telesecundaria) in very remote areas, and provided bilingual instruction in more than 30 indigenous languages. To serve children in the most remote areas, the National Council for the Promotion of Education (Consejo Nacional de Fomento Educativo, CONAFE), or escuelas secundarias, offers classes to as few as five students taught by "community instructors."

You can read more about escuelas unitarias.

To meet the needs of adults and working youth, there is special elementary and secondary schooling in adult education centers and "workers schools." The National Institute for the Education of Adults Instituto Nacional de Educación de Adultos (INEA) provides literacy training, elementary and secondary level classes, as well as job training in Mexico and for Mexican nationals living in the United States. A national system of high school classes called Open High School (Bachillerato Abierto) offers self-paced, academic studies. Compensatory programs provide materials, supplies, and technical support to children and educators in the country's rural and indigenous areas.

You can read more about compensatory programs.

If you are online, you can also visit the website of the Binational Program for more information.

Education programs help meet the needs of the children of migratory farm workers who move within Mexico. Special education has been significantly redefined and offers educational opportunities based on an inclusion model for students with physical or learning disabilities. The Binational Education Program helps assure continuity of studies for students who move across the border with the United States. The Transfer Document for the Binational Student, a bilingual report card negotiated by the federal government of Mexico and various states in the United States, facilitates re-enrollment for these children in Mexican and United States primary and secondary schools Despite admirable achievements, there remain significant challenges.

The National Education Program 2001-2006 (Programa Nacional de Educación, 2001-2006) is an ambitious blueprint for the future of Mexican public education. It affirms, expands, redefines, and proposes new and existing initiatives designed to confront and resolve the challenges faced by Mexican society and education.

For more information, read this discussion of some of the most compelling goals and strategies.

Basic Education

The following discussion is a general description of Mexican Basic, high school, and higher education. For specific information about assisting students, consult Transfer Student Assistance.

You can also view a calendar of the Mexican school year (online).

Mexican basic education is free and secular. It consists of preschool (preescolar), primary (primaria), secondary (secundaria) and teacher training, which is called Normal.

High school follows Secondary. It is not part of Basic Education. Bachillerato usually refers to university preparatory programs. There also are terminal vocational studies, called Técnico Profesional that last from two to four years.

Higher education includes undergraduate, master's, specialist, and doctoral degree academic programs. There are also technological universities. Beginning in 1984, all teacher training programs became four-year, university level studies, granting licenciatura. There also are master's, specialist, and doctoral level degree programs in various fields of education. The chart of educational structure compares the levels of education in Mexico with grade levels in United States schools.

General Characteristics

- National curricula, school calendar, and schedules for Basic Education and Normal schools, report cards, and certificates

- No required attendance zones, transportation, or cafeterias in elementary schools-Some secondary schools may have a cafeteria.

- Multiple sessions in many urban schools

- Uniforms in many public schools

- Parental responsibility for all but the construction of classrooms, teachers' salaries, and books-This includes the purchase of most consumable materials, furniture, and equipment, as well as all maintenance and cleaning.

- Schools where only boys or girls attend-During the last decade most Mexican public primary schools have become co-educational, but there may still be some in rural areas where, by tradition, only boys or girls attend; or there may be a few boys in a session dominated by female students and vice versa. There are still single-sex private elementary schools, as well as single-sex public and private secondary schools.

- Discrepancies in the size and quality of school facilities, especially between rural and urban schools--a few rural schools may lack running water or electricity. Some urban schools may have facilities that include laboratories, a gymnasium, a multi-purpose room, or a library. Most school buildings are organized around a central open area called the Patio Cívico, where routine as well as special events are organized. These may include recess, patriotic assemblies, sports, and dances.

There are no federal laws or guidelines for the use of school uniforms. It is up to the parents and staff of each school to decide if students will use a uniform and what style. The uniform may be as simple as denim pants and a white shirt, or more elaborate. Uniforms are very common, especially in many urban schools where they may be worn every day and where there may even be a dress uniform for special occasions. It is customary for students in small towns to wear uniforms, which they also may use for participation in community parades and other civic events. In some schools, the uniforms are worn just one day a week. Students sometimes wear sports clothes on the days they have physical education.

View a Chart of the Educational Structure in Mexico.

Parental Participation in Mexican School

Parental participation is frequent and vital in Mexican schools. The parents are both required to attend some school activities or meetings and encouraged to participate in others. Because the state usually provides only the buildings and the teachers, the parents sometimes are responsible for all maintenance, repair, and improvements of the facility, as well as the purchase of equipment, furniture, and consumables.

Several groups are formed in each school during the first two weeks of each school term. One of the most important organizations is the Parents’ Association (Asociación de Padres de Familia). All parents, the school principal, and a teacher who serves as the secretary belong to the Association. The parents elect officers and set the yearly dues, which, in some cases, may be paid by contributing in-kind services.

The principal establishes a list of needs and assigns priorities. The appropriate Parent Association committee proposes projects based on the principal’s needs assessment. These projects may include anything from painting some classrooms to the maintenance of bathrooms to the construction of a school library. The Parents’ Association will plan fund-raising events such as raffles, movies, or dances. It will also support social activities, field trips, sports events, and other extracurricular school functions. There are two general meetings a year.

Parents routinely participate in or attend other functions or required meetings. During February parents must enroll their children for the following school year if the child will attend first grade of elementary or first year of middle school. When a student enters a school for the first time, the parent may be asked to sign a contract assuring his or her support for school policies and acknowledging responsibility for the student’s attendance and behavior.

In addition to two general Parents’ Association meetings, parents must attend five meetings a year to receive and sign their children’s report cards. At the elementary level, these meetings will occur in the children’s classrooms. At the middle school level, the meetings may be organized with the school administration. The children usually accompany their parents, and the teachers will review the progress of the entire group, as well as propose and solicit support for school projects.

The teacher or the school administration may call certain parents to the school to respond to problems relating to their child’s attendance, academic performance, hygiene, discipline, or nutrition. Any parent may initiate a school conference to address their concerns.

Traditionally, there is great participation by all the parents in civic events such as celebrations of Mexican Independence or the Revolution, in cultural events, such as dance or music programs, social events including Mother’s Day and Teachers’ Day, sports, or the grand fiestas that celebrate the end of the school year and graduation from elementary or middle school.

The Councils of Social Participation (Consejos de Participación Social) were created as part of the National Accord for the Modernization of Basic Education (Acuerdo Nacional para la Modernización de la Educación Básica) of 1992. The members include school administrators, teachers, students, former students, parents, community members, union representatives, and local political leaders. Their activities overlap somewhat the Parents’ Association, but there are important differences. The purpose of the Councils is to strengthen and improve the quality of education. They promote and support in-school and extracurricular activities such as conferences, theatrical works, sporting events, and community health campaigns. Monies collected from some of these events may be applied to improve school facilities, raise the socio-cultural level of the students, and strengthen the academic program by purchasing materials and equipment.