Cultural Differences Experienced by Transfer Students

Students transferring from Mexican schools face incalculably difficult stresses and barriers. The better we understand these special obstacles, the more likely these students are to become acculturated, learn English, achieve success in school, and contribute to society.

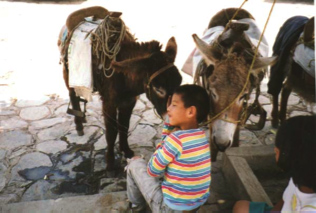

The starting point for any discussion of cross-cultural barriers must begin by emphasizing that the majority of the binational students are from rural areas and understanding the implications. Life in rural Mexico is difficult in part because of the lack of access to public services, including the same educational opportunities that a student may find in urban areas. At the same time, it may be argued that life is less stressful. The child lives, studies, works, and plays in an environment where he or she is surrounded constantly by a large, extended family and persons known by the child. Time may not be measured by clocks. Dietary habits, including the use of utensils, are not the same as for city dwellers. Rural folk in Mexico are sometimes ridiculed by persons from larger towns or cities, who may laugh at their speech, clothing, or mannerisms.

We can only begin to imagine the agony some of our Mexican transfer students, whether from rural or urban areas, suffer when they are forced to leave their friends and familiar, secure surroundings. At least some of the following socio-economic, cultural, and educational differences confront each and every one of these children:

1. The language barrier is the most significant, both for the students as well as their parents.

2. The warm relationship between the teacher and the student, which in Mexico is an extension of the parent-child relationship, especially in pre-school and primary. It is based on mutual respect of the teacher for the student and his parents, in addition to a very strong cultural tradition of respect for teachers, as described below.

3. The treatment of adults and superiors, including parents and teachers, which has been described as a “tradition of respect and submission” The most common misunderstanding prompted by this cultural difference is the lowering of eyes in the presence of an adult or a person in authority. While taught as mandatory behavior to show respect in Mexico, in the United States means guilt!

4. Dietary differences not only in the taste and textures of the food, but also the hours and quantities consumed.

Many students are accustomed to a light breakfast, a snack at about 11:00 a.m., and a heavy meal at home between 1:00 and 2:00 p.m.

5. Living conditions which may be crowded and substandard

6. Climate Depending upon the point of origin in Mexico, the time of year they arrive and the destination area of the United States, families have difficulty acclimating to differences in temperature or humidity. Some students are from semi-arid mountainous regions where it never is hot. Others may be from a warm climate and not used to the cold temperatures.

7. Peer relationships: Transfer students sometimes experience rejection from their new classmates, including other students of Mexican origin.

8. Marked differences in male-female roles, especially for children from rural Mexico, where boys and men do manual labor while girls and women take care of the home. Because the mother now probably has to work in the fields, the children, at a much earlier age, may have to assume household duties, including baby-sitting, house-cleaning, and preparing food.

9. Stereotypical attitudes especially about adolescent behavior and United States high schools, shaped by films and television programs.

10. Significant differences in school facilities, procedures and policies, some of which are as follows:

- Sensory overload: The tendency in the United States to cover walls and available spaces with learning aids creates an overabundance of stimuli for a student from a spartan rural Mexican school.

- Lack of familiarity with computers and other equipment

- Riding a school bus, eating in a cafeteria, renting and opening a locker

- Changing clothes for physical education classes, which is embarrassing for children who have never changed clothes at school, probably have been taught that it is unacceptable, and may not have the appropriate clothes

- Changing classrooms at the middle and high school levels; In Mexico the teachers change classrooms.

- Behavior of faculty and staff: Behaviors shaped by cultural differences and fear of lawsuits may lead Mexican students to believe that United States teachers do not like them. For most Latinos, including Mexicans, the “personal distance,” or the culturally determined distance maintained between people, is much smaller than for Anglos. Mexican children and adults will misinterpret your maneuvering to keep a “comfortable” space between you and them.

- Differences in writing the date and in name usage: All Mexicans have two last names. For an explanation of this and the differences in writing the dates consult Transfer Student Assistance: Understanding Names.

- Distance between home and school: Students often live at much greater distances from their United States schools than they lived in Mexico from their rural or urban schools. They are far from home, and may not know where their parents are working, all of which may contribute to their anxiety.

- Home literacy: Parents of our children of Mexican origin probably did not have available to them the educational opportunities in the Mexico of the 1990’s. Many of them are illiterate, which deepens the communication gap between school and home, making it very difficult to help their children adjust to the new school or help them with their assignments.

- Parental expectations: Parents may expect frequent communication from the school, especially in matters relating to discipline and the distribution of report cards.

- Differences in minimum schooling requirements and expectations: Because in Mexico Secundaria (the equivalent of 7th, 8th, and 9th grades) has only been required since 1993, and school attendance is required until 14 years of age, parents may neither be aware of the compulsory attendance laws in the United States nor understand the expectation that everyone should complete high school.

- Differences in setting up math problem: In some Mexican schools negative integers are written with the symbol above, instead of in front of the number. Long division is calculated as follows, although this process may be changing:

- Different system for naming large numbers: As in many parts of the world, the so-called “English” system is used for naming large numbers. “One billion” is called “one thousand million.”

|

Number |

U.S. System |

English System as used in Mexico |

Scientific Notation |

|

1,000,000,000 |

BILLION |

THOUSAND MILLION |

109 |

|

1,000,000,000,000 |

TRILLION |

BILLION |

1012 |

- Differences in writing styles Mexicans value creativity and innovation, and this is evident in speaking and writing. Do NOT expect topic sentences followed by three supporting statements!

Suggestions for Success

The living conditions, changes in climate, food and the like, combined with the language barrier, nostalgia for relatives and friends, and differences in the schools all make life difficult for our binational youngsters. The following strategies will help educators assist these students and their families:

1. Teach staff members how to pronounce the most common names and a few words of greeting.

2. Implement an orientation for new students, to include the following:

- A tour of the school including the following: locating classrooms, bathrooms, the cafeteria; introductions to key staff, including those who speak Spanish; bus stops

- An explanation of some of the cultural differences, such as the significance of lowering the eyes

- Bathroom protocol

- Finding the locker and learning how to use the lock

- Key phrases in English, such as “May I go to the bathroom?”

Bilingual students could help implement the orientation.

3. Prepare an information packet for the new student’s teachers, counselor, and administrators. This might include a description of the student’s family, home town in Mexico, academic achievement, interests, and the like.