Editing Hamlin Garland |

|

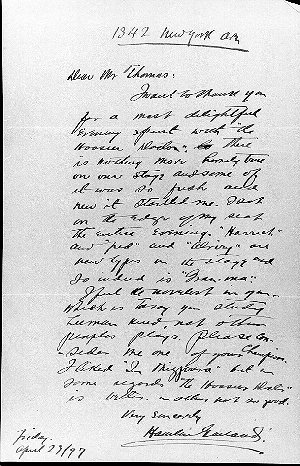

Scholarly editors of letters (those who locate, transcribe, edit, annotate, and then persuade a press to publish the results) have to deal with a plethora of practical and technical problems. Some practical issues range from deciding how many letters to publish, which letters will interest what readers, and the sort--and amount--of annotation to include. More technical concerns include how to present the manuscript letter (facsimile reproduction or edited transcription); and whether and how to present the writer's errors (should one correct typographical or grammatical errors? should one be scrupulously faithful to the manuscript and include exactly what the writer wrote, including cancellations and insertions?). Garland was a prolific writer, publishing over 40 books, as well as being an excessively gregarious man. For the Selected Letters of Hamlin Garland (University of Nebraska Press, 1998), my co-editor (Joseph McCullough of UNLV) and I were faced with task of selecting 405 letters to include in the volume from over 5,000 letters scattered around the country. We intend the edition to be representative of a career that spanned 55 years of letter-writing to over 700 correspondents, who ranged from fellow writers to presidents, from college professors to fans, from artists and musicians to the cultural elite. To illustrate the sort of letters I have grown to know perhaps too well, below is a holograph letter (in the handwriting of the author) to the playwright Augustus Thomas (1857-1934), author of over 60 plays, who was noted for his depiction of American background in such works as Alabama (1891), In Mizzoura (1893), The Capital (1895), and Arizona (1899). Garland had just seen Thomas's The Hoosier Doctor, which opened at the New National Theatre in Washington, D.C., on 22 April 1897. Thomas later became one of Garland's close friends. Garland's handwriting ranges from the merely illegible to the truly hair-pulling, scream-inducing awful. But see for yourself: |

|

1342 New York Ave Dear Mr Thomas: I want to thank you for a most delightful evening spent with "The Hoosier Doctor". There is nothing more homely true on our stage and some of it was so fresh and new it startled me. I sat on the edge of my seat the entire evening. "Harriet" and "Fred" and "Alviry" are new types on the stage and so indeed is "Gran-ma." I feel the novelist in you--which is to say you study human kind, not other peoples plays. Please consider me one of your champions. I liked "In Mizzoura" but in some regards "The Hoosier Doctor" is better--in others not so good. Very sincerely Friday. [this and the following letter are courtesy of Special Collections, Miami University] |

| Aren't you glad for the transcription? | |

|

Fortunately for my eyes, Garland began to use the typewriter more often as he became increasingly involved in cultural affairs. Here's an image of a letter written to Eldon Hill, who was, at the time of this letter (25 January 1938), an eager student writing his dissertation on Garland's life and works. In this letter the 78 year-old Garland explains his boredom with Herman Melville's Moby Dick, which had recently been rediscovered. |

|

|

|

||

| Maintained by Keith Newlin | ||

Last Updated:

09/12/2015