Emslie Lab

Emslie Lab

Funding by:

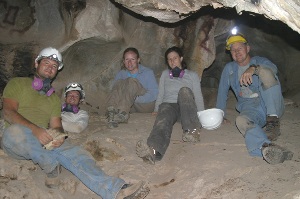

Cement Creek Cave 2007 Excavation Team (plus D. Meltzer, photographer)

|

|

Cement Creek Cave Excavations, 2007

Fossil left mandible in lateral (top) and occlusal (bottom) views of an extinct short-faced skunk (Brachyprotoma sp.) from Cement Creek Cave (top specimen in each photo) compared to B. obtusata (USNM 12045, bottom specimen in each photo) from Cumberland Cave, MD. The p4 is slightly more robust in USNM 12045. Scale = cm.

Dorsal view of fossil 1st phalange of extinct shrub-ox (Euceratherium collinum) from Cement Creek Cave (left) compared with a specimen from Musk Ox Cave, NM (uncat., USNM). Scale = cm.

Dorsal view of bison (Bison sp.) 2nd phalange from Cement Creek Cave (left) with a modern bison phalange (right). Scale = cm.

The entrance to Signature Cave, Colorado.

Profile of excavated pit in Signature Cave.

Subalpine forest is found in the vicinity of

Signature Cave today.

Paleoecology of the Upper Gunnison Basin, Colorado Note: This project was completed in 2015 and no additional research is planned. |

|

This project began in the mid 1990s and focuses on reconstruction of late Pleistocene through Holocene environments in the Upper Gunnison Basin, a montane basin surrounded by high-elevation mountain ranges located in west-central Colorado. This research is being conducted in collaboration with Dr. Mark Stiger, Western State College, Gunnison, CO, and Dr. David Meltzer, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX. Drs. Stiger and Meltzer are archaeologists interested in early human exploitation of and adaptation to post-glacial environments in the basin. My research has focused on reconstructing late Holocene plant communities using packrat middens (Emslie et al. 2005) found throughout the basin and documenting and explaining changes in late Pleistocene through early Holocene small mammal communities based on fossil assemblages in caves (Emslie 1986, 2002). Since 2008, National Science Foundation funding has supported analysis and excavations of vertebrate fossils from two high-elevation caves in the basin that are providing the richest and most diverse late Pleistocene mammalian faunas now known from high-elevation (3000 m, or 9500-10,000 feet) sites in North America. We are using stable isotope analysis of enamel from selected species of fossil and living mammals to investigate paleoclimatic conditions and paleotemperatures in the basin before and after the last glacial maximum (LGM) at ~18,000 years ago. So far we have excavated and identified thousands of vertebrate fossils from these caves that date from >40,000 years old to the present and are now conducting systematic analysis of this material. The links here provide more details on these activities including taxa identified and a description of the excavations. Additional research at these sites will be completed in summer 2010 with undergraduate and graduate students. Cement Creek Cave Test excavations were first conducted in this cave by S. Emslie in June 1998, with funding from the National Geographic Society. No archaeological remains were found in this cave, probably due to its high, small entrance on the limestone outcrop (approximately 3-4 m above ground level, 1 m diameter). Inside this opening, the cave divides into several passages. One of these passages leads downward to a small room, approximately 15 m into the cave, where sediments, fossils, and middens have accumulated (Fig. 1). A 50 x 50 cm test pit was placed in the floor of this deposit and excavated in 10-cm arbitrary levels to a depth of 1.30 m (13 levels). Excavations ceased at this point and the test pit was refilled after covering the bottom with plastic. The unexpected depth of these deposits and the small size of the test pit prevented excavations from continuing to the bedrock floor of the cave. Figure 1. Plan view of Cement Creek Cave showing the location of excavations in 1998 and 2007 (left) and stratigraphic profile (right) of excavated pit in 2007. All sediment from these lower levels was washed through 0.64, 0.32, and 0.025 cm2 mesh screens. Thousands of bones were recovered from the 0.64 and 0.32 cm2 screens, after the washed matrix was dried and sorted for all organic remains using magnifying lamps and a low-power binocular scope. These bones include well preserved and complete jaws of shrews, voles, and ground squirrels, species that are most indicative of local environmental conditions in the past. Radiocarbon analyses on bone indicated an age for the deposits ranging from 43,330 to 1120 14C yrs B.P. from the lower to upper levels, respectively. This relatively well-stratified deposit (some mixing is indicated by the radiocarbon chronology at levels 5/6 and 12/13) has produced the first sequence of vertebrate fossils in Colorado that date before and after the LGM. Of even greater significance, this assemblage is the only known high-elevation fauna in North America that dates to this period/ Two other high-elevation sites, Porcupine Cave, Colorado, and SAM Cave, New Mexico, date entirely within the early to middle Pleistocene, before the LGM (Rogers et al. 2000; Barnosky 2004). The deposits at Porcupine Cave (1.0 – 0.6 Ma) also span at least two glacial-interglacial cycles and provide a model for comparison of faunal turnover with climate change in alpine communities (Barnosky 2004; Barnosky et al. 2004; Barnosky and Shabel 2005).

In summer 2007, excavations were renewed at Cement Creek Cave by S. Emslie and D. Meltzer (Southern Methodist University, SMU) with the assistance of four graduate students from SMU and a local rancher, Don Yeager. A 1x1 m pit was mapped and excavated adjacent to the original excavation in 1998. Excavations proceeded in 5-cm levels with all sediments sifted through three 0.64, 0.32, and 0.025 cm2 mesh screens. The 1998 backfilled pit was relocated and an additional .5x.5 m section was excavated to expand the total excavated area to 1x1.5 m. While most upper levels (top ~50 cm) were found to be largely disturbed by cavers in the past (a .5x.5 section was found intact and undisturbed), the lower sediments were intact and rich in vertebrate fossils. The excavations continued for 10 days before stopping at level 40 at a depth of 2.2 m, or 1 m deeper than the excavations in 1998. The cave floor was never found, but probing indicated that the sediments probably continue for at least 15-20 cm below level 40. The unexpected depth of the sediments, time limitations in the field, and concerns about wall collapse led us to stop excavations here and backfill the pit. A new stratigraphic profile of the deposits (Figs. 1-2) indicate that they consist of dry to moist and degraded packrat midden in the top 60 cm (levels 1-12), and cave sediments and rock spalls in the lower deposits (levels 13-40) that abruptly change from dark to light brown in color with depth. Undisturbed portions of the upper levels are rich in macrobotanical remains (sticks, leaves, needles, and cones) and bones, and date to the late Holocene. The lower sediments are significantly older, and are rich in vertebrate fossils, especially rodents. Bones of larger mammals (bison and other artiodactyls), birds, and reptiles also were recovered.

Figure 2. North wall of pit (top) exposed after completing new excavations in 2007 with a close up (bottom) of the distinct break from darker to lighter sediments at ~60 cm below the surface and the thin white upper travertine layer at ~80 cm depth.

Two thin travertine layers exposed in these new excavations indicate distinct breaks in cave sedimentation in the Pleistocene (Fig. 2). The upper travertine layer is at a depth of ~80 cm below the surface and near the bottom of the 1998 test pit dated at 43,330 B.P. The lower travertine layer is at a depth of 1.3 m. Attempts to date bones from above and below both travertine layers failed for lack of enough collagen and it is likely that U-series dates will be needed to determine the age of these layers.

Previous identification of microfauna from the 1998 sample from Cement Creek indicates that the lower levels contain a high diversity of vertebrate taxa with approximately 30 species identified to date (Table 1). At least six species of shrews (Sorex spp.) are represented, most of which currently occur in the UGB (Emslie 2002). One of the most interesting species recovered so far is the Preble’s Shrew (Sorex preblei), today found only in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho with one specimen reported from Black Canyon, Colorado, outside of the Basin (Fitzgerald et al. 1994). The record from Cement Creek Cave includes two right mandibles that are recognized as S. preblei by their small size, relative depth of the dentary below the m1 equal to or greater than the height of m1, and position of the mental foramen (Harris and Carraway 1993; Carraway 1995). Little is known on this species, but most modern records from Montana are from dry, sagebrush/grassland habitats (Hoffmann and Pattie 1968). That this type of habitat once occurred near the cave is supported by the association of other vertebrate taxa, including white-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii) and sagebrush vole (Lemmiscus curtatus), in the same stratigraphic level (level 10). Only two other fossil records for this shrew are known from late Pleistocene cave deposits in southern New Mexico where similar paleoenvironmental interpretations were applied (Harris and Carraway 1993).

Since completing the excavations in 2007, analysis and identification of the fossil material has been ongoing. Due to the sheer volume of bone in these deposits, only fossils from selected levels could be processed in detail. Accordingly, every fifth level was analyzed from the bottom of the deposits (level 40) to the top (level 5) with all identifiable teeth, including isolated teeth, identified to the lowest possible taxonomic category (level 26 was used instead of 25 in this analysis due to inadvertent loss of fine sediments from level 25). This detailed analysis was completed by S. Emslie with assistance from SMU graduate student Andrew Boehm in 2010 (Table 1). In addition, a series of radiocarbon dates on teeth and bone were completed on selected taxa throughout the stratigraphic deposits and indicate that the fossil assemblage spans at least the past 45,000 years, and possibly extend to 60,000 or more years in age, considerably older than fossil material recovered from Haystack Cave, also in the UGB (Emslie 1986, 2002; Nash 1987; Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Radiocarbon results on fossil bone from Cement Creek (circles) and Haystack Cave (triangles) by stratigraphic level. Bone below level 30 at Cement Creek Cave did not produce dates as specimens were too old. |

Table 1. Taxa identified from every fifth level at Cement Creek Cave, Colorado. Numbers represent total number of identifiable specimens (NISP) and minimum number of individuals represented per taxon (MNI, in parentheses). Taxa identified from other levels, not listed here, include Preble's shrew (Sorex preblei), extinct short-faced skunk (Brachyprotoma sp.), bison (Bison sp.), and extinct shrub-ox (Euceratherium collinum).

Level |

||||||||

Taxon |

40 |

35 |

30 |

26 |

20 |

15 |

10 |

5 |

Amphibia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Anura |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

||

Reptilia |

||||||||

Serpentes |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Aves |

||||||||

Anas sp. |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Phasianidae |

1 |

|||||||

Ptarmigan (Lagopus sp.) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Blue Grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) |

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

||||||

Passeriformes |

5 |

|||||||

Insectivora |

||||||||

Montane Shrew (Sorex monticolus) |

1 (1) |

2 (1) |

5 (2) |

2 (1) |

||||

Dwarf Shrew (Sorex nanus) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Masked Shrew (Sorex cinereus) |

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

||||||

Water Shrew (Sorex palustris) |

2 (2) |

3 (2) |

2 (1) |

1 (1) |

||||

Shrew (Sorex sp.) |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

||||

Chiroptera |

1 |

|||||||

Lagomorpha |

||||||||

American Pika (Ochotona princeps) |

24 (4) |

55 (7) |

48 (6) |

49 (6) |

9 (2) |

16 (2) |

4 (1) |

|

Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus) |

3 (1) |

2 (1) |

5 (1) |

1 (1) |

5 (1) |

2 (1) |

2 (1) |

|

Cottontail (Sylvilagus sp.) |

|

1 (1) |

||||||

White-tailed Jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii) |

2 (1) |

3 (1) |

8 (1) |

13 (1) |

6 (1) |

1 (1) |

||

Rabbit (Lepus sp.) |

1 |

|

4 |

|||||

Leporidae |

3 |

1 |

||||||

Rodentia |

||||||||

Least Chipmunk (Tamias cf. T. minimus) |

1 (1) |

7 (3) |

3 (2) |

7 (2) |

1 (1) |

2 (2) |

2 (1) |

|

Yellow-bellied Marmot (Marmota flaviventris) |

8 (2) |

13 (2) |

21 (2) |

16 (2) |

37 (6) |

3 (1) |

||

Wyoming Ground Squirrel (Urocitellus elegans) |

29 (5) |

67 (6) |

51 (5) |

87 (9) |

27 (5) |

19 (3) |

1 (1) |

|

Golden-mantled Ground Squirrel (Callospermophilus lateralis) |

6 (2) |

10 (3) |

7 (2) |

6 (2) |

1 (1) |

|||

Chickaree (Tamiasciurus cf. T. hudsonicus) |

2 (1) |

2 (2) |

||||||

Pocket Gopher (Thomomys sp.) |

14 (3) |

18 (3) |

21 (4) |

40 (5) |

8 (3) |

18 (3) |

22 (5) |

7 (2) |

Mouse (Peromyscus sp.) |

17 (4) |

6 (3) |

10 (4) |

13 (3) |

4 (2) |

12 (5) |

9 (6) |

2 (1) |

Bushy-tailed Woodrat (Neotoma cinerea) |

23 (3) |

36 (5) |

60 (9) |

25 (6) |

21 (4) |

19 (3) |

16 (3) |

5 (2) |

Southern Red-backed Vole (Myodes gapperi) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Heather Vole (Phenacomys intermedius) |

6 (1) |

26 (4) |

33 (8) |

22 (4) |

8 (3) |

14 (4) |

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

Long-tailed Vole (Microtus longicaudus) |

|

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

3 (2) |

|||

Meadow Vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) |

4 (2) |

4 (2) |

3 (2) |

5 (2) |

60 (10) |

6 (2) |

||

Montane Vole (Microtus montanus) |

1 (1) |

11 (4) |

||||||

Sagebrush Vole (Lemmiscus curtatus) |

9 (5) |

17 (5) |

17 (7) |

9 (6) |

11 (5) |

6 (3) |

7 (4) |

2 (1) |

Western Jumping Mouse (Zapus cf. Z. princeps) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Carnivora |

||||||||

Canidae |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Black Bear (Ursus americanus) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Bear (Ursus sp.) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Short-tailed or Least Weasel (Mustela erminea or M. nivalis) |

5 (2) |

1 (1) |

||||||

Long-tailed Weasel (Mustela cf. M. frenata) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Weasel (Mustela sp.) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||||

Perissodactyla |

||||||||

*Horse (Equus sp.) |

1 (1) |

|||||||

Artiodactyla |

1 |

1 |

||||||

Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis) |

1 (1) |

1 (1) |

The species identified in the fossil record of Cement Creek Cave so far indicate very little change in small-mammal community structure from the oldest levels, dating >45,000 B.P., to approximately levels 5 and 10 which date to the early Holocene (Table 1). These taxa reflect a non-analog, mixed community of open sagebrush grassland and alpine tundra. This community is best described as a sagebrush steppe-tundra and data on fossil pollen from Colorado also support that sagebrush was intermixed with alpine species during the late Pleistocene (Legg and Baker 1980). The resilience of this community across a major climatic event (the LGM) is remarkable and reflects strong community inertia (McGill et al. 2005) and tolerance to temperature changes in high-elevation species (e.g., Millar and Westfall 2010). The most notable extant taxa from this site include the sagebrush vole (Lemmiscus curtatus), no longer found in the UGB, the Wyoming ground squirrel (Urocitellus elegans), which only recently has reinvaded the basin, and the Preble’s shrew (Sorex preblei), identified from several specimens, which currently occurs in open sagebrush habitat in northwestern Colorado and Wyoming. All three of these species apparently were extirpated from the UGB at the end of the Pleistocene, possibly due to fragmentation of their habitat and upward expansion of forested communities with early Holocene warming at ~11,000 B. P. (Fall 1997a, 1997b). By the early Holocene, taxa more typical of a subalpine forest community begin to appear including red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) and red-backed vole (Myodes gapperii), both of which occur in the upper levels of Cement Creek Cave and the lowest, or oldest, levels in Signature Cave (see below) as well as in the region surrounding these caves today. Pygmy shrew (Sorex hoyi) and Merriam’s shrew (S. merriami) also appear for the first time in the lower level of Signature Cave.

Signature Cave

In summer 2009 S. Emslie, D. Meltzer, and two undergraduate students from UNCW excavated a 1x0.5 m pit in a second cave, Signature Cave, located near Cement Creek Cave at a slightly higher elevation using the same methodology. The deposits in this cave, excavated to 34 levels, so far are strictly Holocene in age (~7000 B.P. to the present) and provide a complimentary set of data on high-elevation vertebrates in the UGB that match species found in the region today.

Detailed analysis has been completed so far only on fossils from the oldest level 34, which date from 5000-7000 B.P. The data indicate a vertebrate fauna that, unlike Cement Creek Cave, reflects a subalpine forested community similar to the environment surrounding the cave today. The most notable differences between these faunas include a greater abundance of red-backed vole (Myodes gapperi) and meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus), as well as the first appearance of pygmy and Merriam’s shrews (Sorex hoyi and S. merriami), at Signature Cave. Further results on the analyses of fauna from this cave are forthcoming.

References

Barnosky, A. D., Ed. 2004. Biodiversity Response to Climate Change in the Middle Pleistocene. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley.

Barnosky, A.D., and A.B. Shabel. 2005. Comparison of mammalian species richness and community structure in historic and mid-Pleistocene times in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 56(Supp. I, no. 5): 50-61.

Barnosky, A. D., C. J. Bell, S. D. Emslie, H. T. Goodwin, J. I. Mead, C. A. Repenning, E.Scott, and A. B. Shabel. 2004. Exceptional record of mid-Pleistocene vertebrates helps differentiate climatic from anthropogenic ecosystem perturbations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101: 9297-9302.

Carraway, L. N. 1995. A key to recent Soricidae of the western United States and Canada based primarily on dentaries. Univ. of Kansas Natural History Museum Occasional Papers 175: 1-49.

Emslie, S. D. 1986. Late Pleistocene vertebrates from Gunnison County, Colorado. Journal of Paleontology 60 (1): 170-176.

Emslie, S. D. 2002. Fossil shrews (Insectivora: Soricidae) from the late Pleistocene of Colorado. Southwestern Naturalist 47: 62-69.

Emslie, S. D., M. Stiger, and E. Wambach. 2005. Packrat middens and late Holocene environmental change in southwestern Colorado. Southwestern Naturalist 50: 209-215.

Fall, Patricia. 1997a. Timberline fluctuations and late Quaternary paleoclimates in the southern Rocky Mountains, Colorado. GSA Bulletin 109: 1306-1320.

Fall, Patricia. 1997b. Fire history and composition of the subalpine forest of western Colorado during the Holocene. Journal of Biogeography 24: 309-325.

Fitzgerald, J. P., C. A. Meaney, and D. M. Armstrong. 1994. Mammals of Colorado. Denver Museum of Natural History.

Harris, A. H. and L. N. Carraway. 1993. Sorex preblei from the late Pleistocene of New Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist 38: 56-58.

Hoffmann, R. S. and D. L. Pattie. 1968. A guide to Montana Mammals. Univ. of Montana Printing Services, Missoula.

Legg, T. E., and Baker, R. G. 1980. Palynology of Pinedale sediments, Devlins Park, Boulder County, Colorado. Arctic and Alpine Research 12: 319-333.

McGill, B. J., E. A. Hadly, and B. A. Maurer. 2005. Community inertia of Quaternary small mammal assemblages in North America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102: 16701-16706.

Millar, C.I. and R.D. Westfall. 2010. Distribution and climatic relationships of the American pika (Ochotona princeps) in the Sierra Nevada and Western Great Basin, U.S.A.; periglacial landforms as refugia in warming climates. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research 42: 76-88.

Nash, D. T. 1987. Archaeological investigations at Haystack Cave, central Colorado. Current Research in the Pleistocene 4: 114-116.

Rogers, K. L., C. A. Repenning, F. G. Luiszer, and R. D. Benson. 2000. Geologic history, stratigraphy, and paleontology of SAM Cave, north-central New Mexico. New Mexico Geology 22(4):89-117.