1898 riot falsely depicted in the national

press as

a black riot, Collier's Weekly, Nov.

26, 1898

In fact that the violence had been directly almost entirely toward blacks; whites had illegally arrested and exiled black and white citizens at gunpoint; and the violence had been a coup d'etat, the overthown of the democratically elected city government and the establishment of white supremacy as the ruling force in the state. These facts were all ignored in the spin that white novelists and historians would put on 1898.

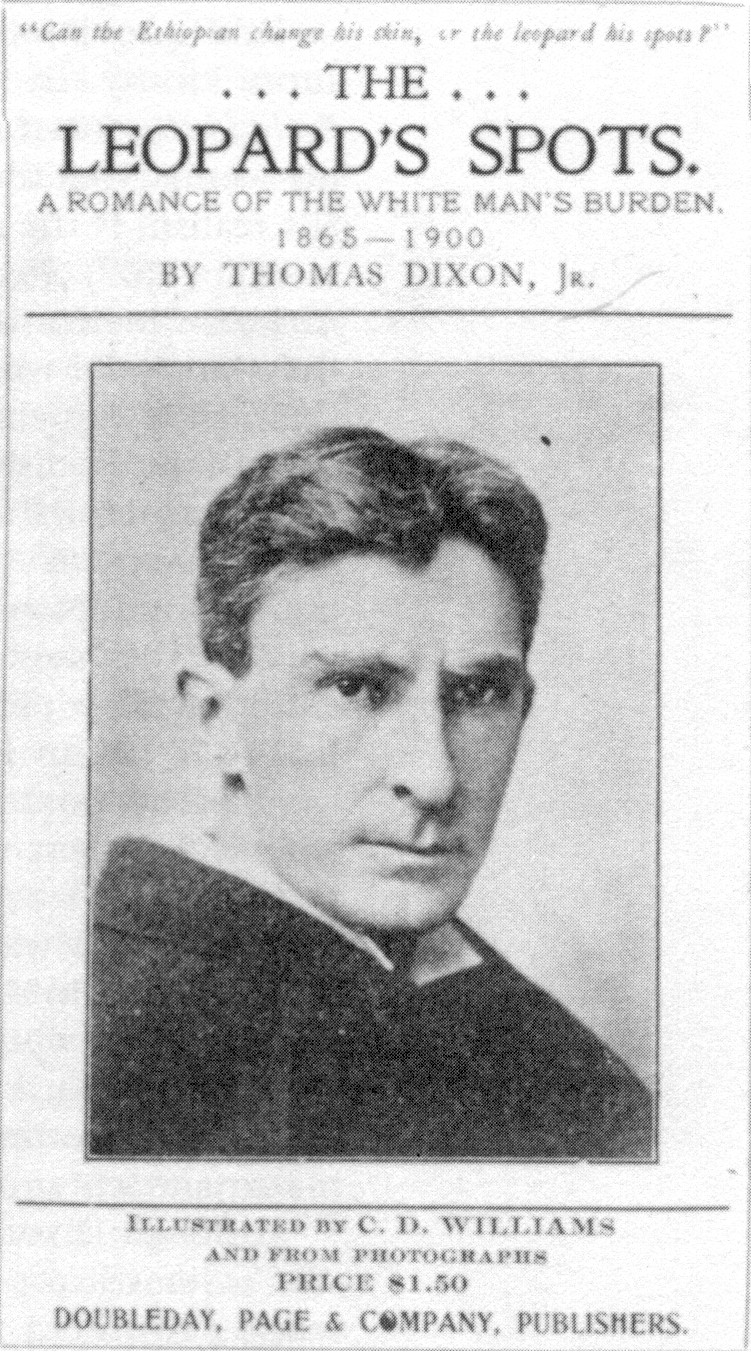

The first and perhaps most influential portrait of 1898 to become known nationwide--aside from the Collier's Weekly article--was a novel by the infamous Thomas Dixon called The Leopard's Spots. (The title aludes to the idea that the innate blemishes of "savagery" in the African, like the spots of a leopard, can never be removed.)

Dixon's white supremacist version of the 1898 revolution pictured it as an act of Christian manliness against a corrupt black and "carpetbagger" regime, which threatened not only business and law, but also white women. The hero of the novel was modelled on Governor Charles Aycock, who presided over the institutionalization of white supremacy in North Carolina. Dixon's racist vision would later be immortalized in the notorious but enormously influential 1915 film by D. W. Griffith, "The Birth of a Nation," which drew both on The Leopard's Spots and on another Dixon novel, The Klansman.

The romantic, racist vision of 1898 soon was confirmed not only in the popular imagination, shaped by Dixon's and other white supremacist art, but also in the popular and even academic understanding of history. In Wilmington, the version of the events of 1898 that would be learned by every white child for decades to come was told by James Sprunt in his local history, Cape Fear Chronicles:

These words reflect accurately what historians have only recently begun to appreciate once again. The so-called "riot" of 1898 was indeed a "revolution" involving "a thorough reorganization of the social and political conditions." The Wilmington revolution of 1898 marked the rebirth of white supremacy, of a society governed through and through by racial hierarchy, reinforced by violence. It was in this racial violence that the city of Wilmington and the state of North Carolina were reborn. The new social order would prevail through most of the twentieth century."The year 1898 marked an epoch in the history of North Carolina, and especially the city of Wilmington. Long continued evils, borne by the community with a patience that seems incredible, culminated, on November 10, in a radical revolution, accompanied by bloodshed and a thorough reorganization of social and political conditions. It was only under stern necessity that the action of the white people was taken, and while some of the incidents were deplored by the whites generally, yet when we consider the peaceable and amicable relations that have since existed, the good government established and maintained, and the prosperous, happy years that have marked the succeeding years, we realize the results of the Revolution of 1898 have indeed been a blessing to the community."

The loss of truth led also to a blunting of vision. The racist simply could not place himself in the perspective of his victims. Racial paternalists like Mr. Sprunt never considered that African Americans would not have regarded their political and economic oppression "a blessing to the community." Were they not subject to that [white] community, rather than part of it?

return to Table of Contents

Link to 5.5:

THE ERA OF SEGREGATION