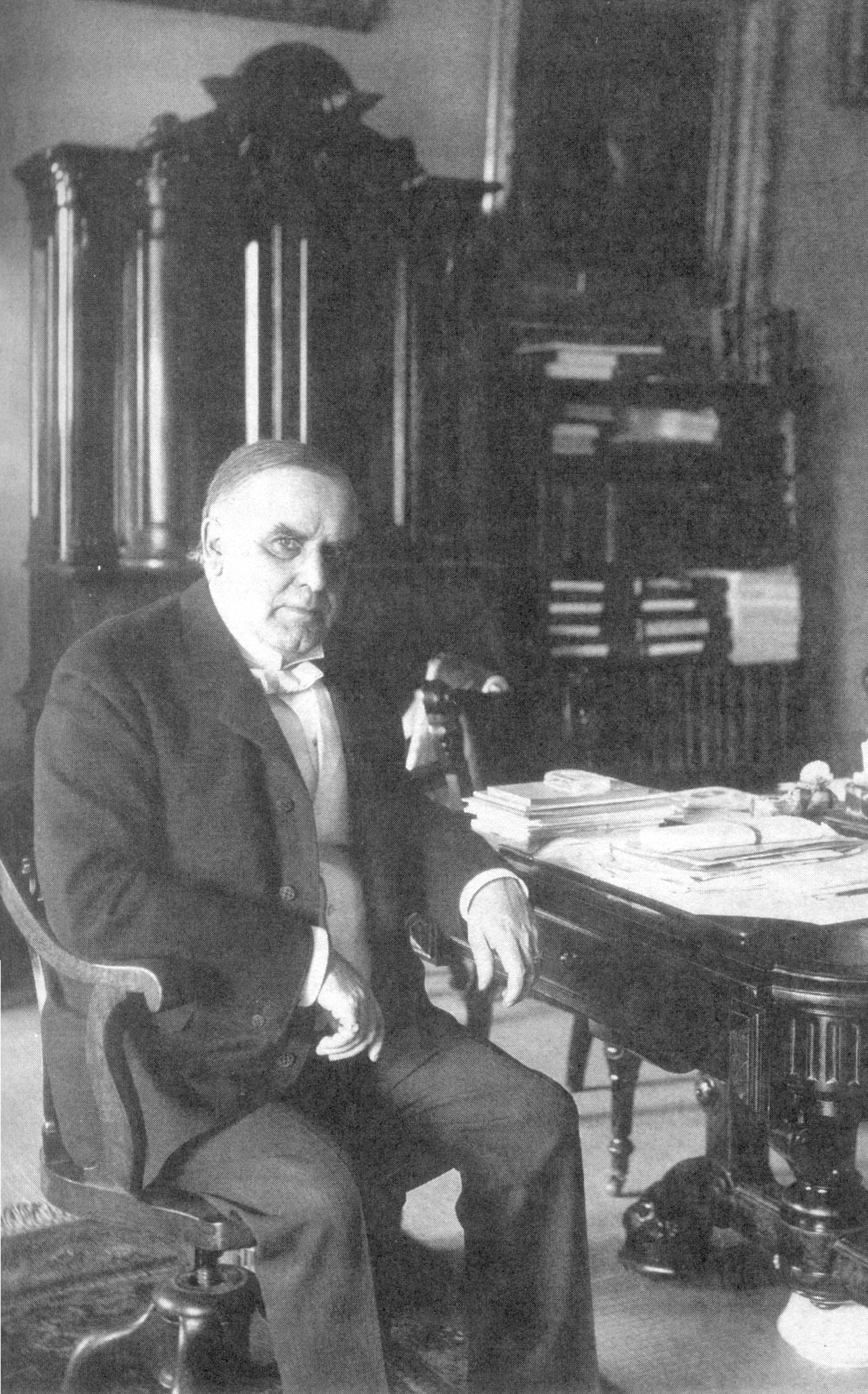

President William McKinley,

in the summer of 1898

Would President McKinley use his authority to intervene militarily to restore law and order and depose the revolutionary government?

McKinley conferred with his cabinet, including the Secretary of War Russell Alger, and the Attorney General John Griggs, but in the end decided not to do anything. Governor Russell of North Carolina, apparently frightened into submission by what amounted to a statewide white racist uprising, never officially requested assistance. McKinley, perhaps sensing the popularity of the Wilmington actions among whites and fearing that any intervention might further aggravate racial conflict, also chose silence. Letters written to protest the racial violence went unanswered.

The implications of this decision and of the Wilmington insurrection have not been fully appreciated. Just as the Supreme Court decision in the Plessey case of 1896 contributed, as a legal precedent, to the spread of "separate but equal" Jim Crow laws throughout the South, so the Wilmington Revolution of 1898 and its acceptance by the federal government contributed, as a political precedent, to the spread of violence to end black civil and political rights throughout the South. The white men of Wilmington had shown their "manhood" by overthrowing the "black" government and defying the federal government to do anything about it. Radical racists throughout the South saw the lesson, and knew they were free to use any means they thought necessary to re-subdue the Negro.

Letters

written to President McKinly protesting the riot and coup

Previous

page

return to Table

of Contents