September 6, 2006

FDA Ruling Puts Pharmacists in Crossfire

by Daniel C. Vock

Stateline.org

The latest fireworks over the "morning-after pill"

weren't in Congress, or at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in

After months of controversy and a flood of 16,000 comments,

the board followed Gov. Christine Gregoire's (D)

suggestions and refused to give legal protections to pharmacists who for moral

reasons object to dispensing the high-dose birth control pill.

The action, though, doesn't end the tempest in

As

"What this does is shift the burden from doctors with

prescribing rights and privileges to pharmacists," said Deirdre McQuade, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops'

spokeswoman on birth control matters.

"We had been putting our efforts into preventing the

FDA from doing this.

Now it seems like it's going to be a state-based matter,"

McQuade said. She added, however, that the conference

hadn't yet decided what action to take at the state level.

Emergency contraception is controversial because it poses

moral questions similar to those raised in the abortion debate.

The Catholic bishops and others who believe life begins at

conception object to Plan B because of the possibility that it may prevent a

fertilized egg from implanting on the uterine wall.

But those who want greater access to the morning-after pill

argue that the drug works the same as standard oral contraceptives, primarily

by preventing fertilization of a woman's egg. Taken within 72 hours of

unprotected sex, the pill can prevent 89 percent of pregnancies, according to

Plan B's manufacturer, Duramed, a subsidiary of Barr

Pharmaceuticals Inc.

A multi-state issue

Like

Pharmacists have lost their jobs in

Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney (R), a possible presidential

contender for 2008, touched off a furor when his administration suggested that

Catholic hospitals would not be subject to a state law mandating that emergency

rooms offer emergency contraception to rape victims. He quickly reversed that

stance.

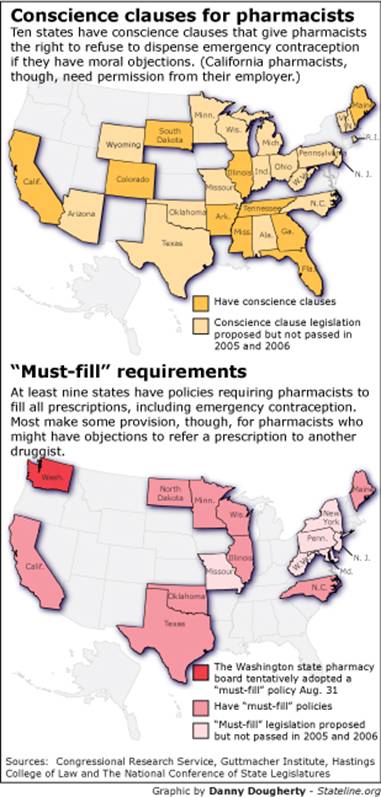

States are split over whether to give priority to health

care providers who have ethical concerns or to women seeking contraception.

Four states

In addition,

The Washington Board of Pharmacy at first considered

enacting a conscience clause but reversed course after the governor weighed in.

If Gregoire's proposal receives final approval early

next year,

The American Medical Association passed a resolution last

year calling on pharmacists to fill all prescriptions. It even suggested that,

if no pharmacist within 30 miles of a patient would fill a script, the patient

should be able to buy the drug from the doctor instead.

New policy questions

The FDA's decision leaves states with even more questions to

resolve: Should stores be required to stock Plan B, now that it's a

non-prescription drug for women over age 18? Will pharmacy technicians, along

with druggists, be covered by conscience clauses? And should other states

follow the lead of nine states that currently let girls under 18 get the drug

without seeing a doctor?

These questions fall to the states because, while the FDA

regulates medicines, states police the doctors who prescribe drugs and the

pharmacists who dispense them.

In its long-delayed decision, the FDA on Aug. 24 agreed to

allow women age 18 and over to buy Plan B without a prescription, but kept the

prescription requirement for girls 17 and under. The manufacturer can sell the

drug only to stores and clinics where a pharmacist works. The medicine must be

kept behind the counter, and store employees must verify the age of the

purchaser. Men can pick up the drug, if they are old enough, for their

girlfriends, wives or other women.

When layered over existing state laws, the FDA rules create

new wrinkles.

Nine states already allow specially trained pharmacists to

give emergency contraception to patients who haven't visited a doctor.

Druggists are allowed to partner with doctors or to follow state regulations to

essentially write prescriptions for the drug on their own.

Under those arrangements, girls under age 18 in Alaska,

California, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Vermont

and Washington may continue to get Plan B without seeing a physician.

The absence of a prescription requirement for women over 18

also could affect the already contentious debates over whether emergency rooms,

especially at Catholic hospitals, should be required to give the pill to rape

victims who desire it.

Seven states, including

Conscience clause issues also might be raised about other

pharmacy employees behind the counter. Lawmakers in

The FDA's unique arrangement that makes Plan B

non-prescription for women 18 and over but prescription for younger females

poses new policy questions in

Michael Patton, executive director of the Illinois

Pharmacists Association, said the FDA action could trump an administrative rule

imposed in April 2005 by Gov. Rod Blagojevich (D) that requires pharmacies that

stock other contraception to carry the morning-after pill.

"It's kind of like if I decided I didn't want to handle

Robitussin cough medicine. There is nothing in the law that would require me to

handle something that is not prescription-driven," he said.

But Sue Hofer, a spokeswoman for the Illinois Department of

Financial and Professional Regulation, which issued the rule, disagreed. Plan B

is still a prescription drug for girls, so the stocking requirements still will

apply, she said.

While

Since 1977,

Four pharmacists fired by Walgreen's last year for saying

they wouldn't dispense emergency contraception are challenging their

termination; their complaint is now with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission. Other pharmacy owners who worry they could lose their stores are in

court challenging the governor's rule mandating that they stock the

morning-after pill.

History of

conscience clauses

The controversy over women's access to Plan B has

parallels in the abortion debate, not just in principles but in tactics.

The introduction of Plan B as a prescription drug in 1999

and the manufacturer's application to the FDA in 2003 for over-the-counter

sales -- sparked a renewed interest in conscience clauses, which first cropped

up following the U.S. Supreme Court's 1973 Roe. v. Wade decision legalizing

abortion.

According to the Congressional Research Service, the first

conscience clause to become law was passed by Congress in 1973.

The so-called Church Amendment named for U.S. Sen. Frank

Church, D-Idaho prohibited officials from forcing federally funded

health-care providers to perform abortions. Since the mid-1990s, Congress has

passed numerous other restrictions to ensure that health-care professionals and

insurance programs aren't forced to participate in abortions.

Most recently, Congress began attaching a Hyde-Welden Amendment to appropriation bills in 2004. It bars

government agencies from treating health-care providers differently for

refusing to perform or pay for abortions.

States rapidly adopted conscience clauses mostly for

abortion after the Church Amendment.

Today, 46 states specifically give doctors the right to

refuse to perform abortions, according to the Guttmacher

Institute. By comparison, 16 states similarly shield doctors who object to

performing sterilization, and nine have laws allowing doctors to refuse to

prescribe contraception.

Plan B is distinct from the abortion pill RU-486. The abortion pill can terminate pregnancies for up to seven weeks, whereas emergency contraception will have no effect on an embryo that already has attached to the uterus. Pharmacists cannot dispense the abortion pill, because it must be taken in the presence of a doctor.