Gender, Power, Deity,

Magic

Assignments from Previous Classes

|

Tuesday, Nov. 22: Virgil, Aeneid 1-6 |

|

Preparation for Class Discussion

- The affair between Dido and Aeneas is

tragic for her, but is it tragic for him? Is he as unhappy to leave

her as she is for him to leave? Is he unhappy at all? Does he

ever really love her? If so why is he so complacent about leaving?

How does he feel when he sees her in the underworld? What does this

say (if anything) about their relationship when she is alive?

- In what ways is Dido deluded about the

relationship, and to what extent is that delusion the work of the gods?

Is she in any way parallel to Phaedra, who was also deluded by Aphrodite and

ended up committing suicide? Where are the similarities and

differences?

- Aeneas has several emotional

relationships that may or may not be deep. What do you see about his

relationship with his wife, his father, his son, his friend A, his mother

(Venus/Aphrodite), Dido, his crew members, and anyone else you can think of?

- Aeneas ends up in several of the same

places Odysseus does, on the verge of some of the same encounters. How

does he react to them differently from the reactions and experiences of

Odysseus? What does this show about him as a hero and a leader?

- What view of the afterlife does Aeneas'

underworld journey show? How does this view affect the world of the

living (or how we as readers feel about it, as we emerge through the ivory

gate?

- Do you like Aeneas? More or less

than Odysseus and/or Achilles?

|

Thursday, Nov. 17:

No class BUT

Begin Virgil, Aeneid 1-3

See writing assignment below |

|

Writing

Assignment due Nov. 22

Description:

This is a 1-2 page paper. It counts for a quiz grade (though see below).

Your response, no research involved. I do not expect you to spend more

time on it than you would spend in our missed class (i.e. 75 minutes).

Topic: Aeneas’ Account of the Fall of Troy, Aeneid 2-3, and the

Iliad.

This account by Aeneas is delivered to the Carthaginians at a

feast given by Queen Dido, who is falling madly in love with him (through a

strange collusion of Venus and Juno, usually at odds with one another). Here

Virgil is engaging in a “dialog” with the Iliad, with which every elite

Roman was familiar whether in the original Greek or in Latin translation. So

how does Aeneas’ perspective relate to (e.g. support, undermine, cast new light

on, etc.) the Iliad? Consider such things as portrayals of the

characters (Greek, Trojan, male, female); accounts of potential or actual

heroism or cowardice, the value and meaning of violence, ideas of necessity,

fate and the gods’ will; ideas of fame and oblivion; the meaning of a city’s

destruction; morality and survival, etc.

Approach:

You can focus on one or more of these issues or involve others of your own. You

should have a thesis statement and support your arguments with references to the

works.

Rubric:

-

A =

A supportable overall theme in your discussion, carried out along several

lines of evidence/several related situations/events; good overall

comprehension of both works; specific examples to support your points, a

satisfying conclusion.

-

B =

The same as A, but not fulfilled as well in one or more particulars

-

C =

Attempting the A categories, but without as complete awareness of the works

and their themes and context, or argumentation that is not as specific or

effective as it should be, or a proportion of comments that do not get

beyond simple comparisons.

-

D/F =

comments without a thematic overview, or that do not go beyond simple

comparisons of events and situations; inaccuracies and misconceptions that

undermine arguments; lack of awareness of the works and underlying context.

Extra Credit:

Up to 50 points extra credit on your quiz grade will be awarded to well

thought out, well-argued A papers with well-chosen, effectively interpreted

quotes, particularly good argumentation, and conclusions that go above and

beyond the call of necessity.

|

Tuesday, Nov. 15:

Reading:

- Alexander Histories (linked

below) NOTE: Although there are a lot of readings marked, all

of them are brief anecdotes.

|

|

Background:

Alexander's Birth:

-

Alexander Romance:

This is an English version that is fairly close to

the 4th century CE Latin text I am not sufficiently crazy to try to translate

for you. Read from the beginning to the bird laid on Philip (about 6

pages).

- Plutarch:

Alexander's birth

Both of the accounts (the later, more

fanciful Alexander Romance and Plutarch’s) show an element of omens, and the

interest of divine beings in Alexander’s birth. Where are the similarities, and

where are the differences, and to what effect does each text use the description

of the supernatural?

Character

Anecdotes:

These accounts of

Alexander's actions are generally legitimate attestations of things that

happened, but they are also told in a way that seem anecdotal, and that provide

a view of Alexander's character that explains his remarkable success in warfare

-- and to some extent, the habits of mind and the dynamics of his relationship

with his men, allies and enemies that account for his difficulties as well as

his triumphs. From these anecdotes, what impression of Alexander's

character emerge? Are there significant variations in how he is portrayed?

Are these recommendations of appropriate or acceptable or admirable traits for

ordinary people, or do they reflect something that only works for Alexander

(e.g. as Achilles and Herakles also played by their own rules)? As a

modern reader, what is your assessment of Alexander from these anecdotes, and

based on what you know about Greek perspectives on power, do you think it aligns

with the attitude a Greek would have?

Resources:

Alexander the

Great on the Web: A comprehensive site, from which most of the links here

are made.

|

Thursday, Nov. 10:

Reading:

|

|

Preparation for Class discussion:

The Magical Papyri linked above (and also

handed out in class) have the discussion questions attached. Basically, we

are looking at this as practical magic, and exploring the sources of magical

actions (in materials, time, intention) and the relationship between the divine,

semi-divine, and human worlds; power is an issue as well.

If I get the Alexander Romance up tomorrow,

we will also look at the Nectanebo section of that (where an Egyptian ex-king

and magician magically becomes the father of Alexander the Great).

|

Tuesday, Nov. 8:

Reading:

|

|

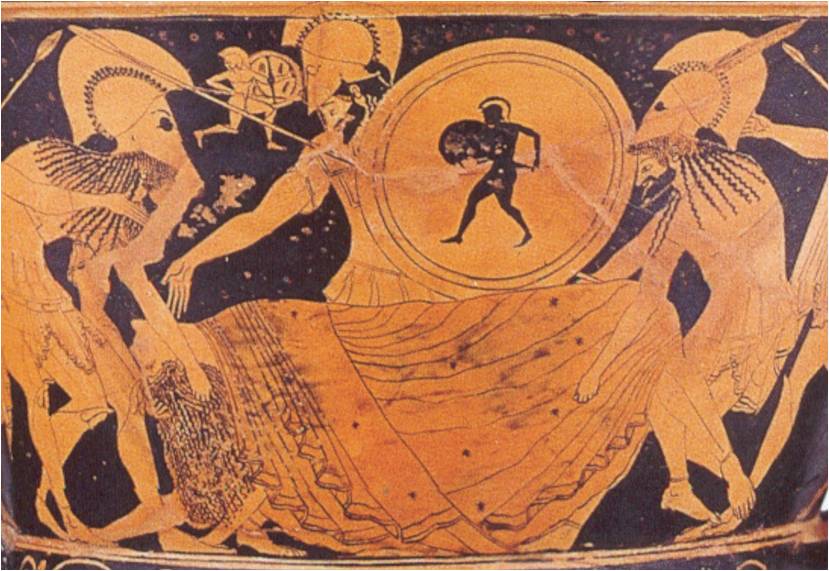

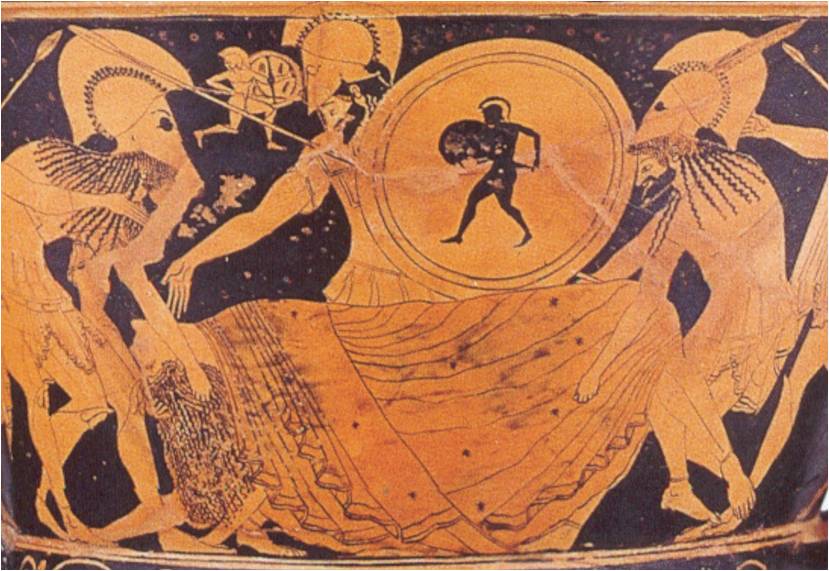

Theoi.com readings: Go to Olympian

gods, then Athena. Look over the "favor" and "wrath" sections,

choose a few myths in which heroes are favored (or wrathed?), and look

at what inspired Athena's favor or wrath.

Preparation for Class discussion:

- We will continue with the Herodotus

reading, so review those questions and be prepared to respond to them.

- Look over the terms from last time as

well as those for this session (posted Friday)

- We will discuss the favor/wrath stories

about Athena you've looked up on Theoi.com, SO BE PREPARED to share one (or

more). Pick a couple, cut and paste them to a document, and print them

out or make them otherwise available to yourself on the media of your

choice. *

*For

those who want to read things on their phones, you can make a mobi document from

an MS word document or pdf using a free program called Mobipocket Creator.

I use this all the time and wouldn't be without it. So convenient.

Terms and Names

- Perseus

- Herakles

- daimon

- demotic

- hermetic

Essay due

Preparation for Class Discussion

Herodotus:

- Look for themes of miasma, hubris,

nemesis, prophecies, trying to change fate, limits of human understanding,

pity and terror, figures of wisdom, changes of perspective, wisdom from

suffering ...

- To what extent is the story of Croesus

like and unlike those of tragic heroes who meet with similar destructions?

- How does history (as opposed to drama

and myth-oriented literature) end up this way?

Thucydides:

- What are the moral effects of the

plague?

- What are the different arguments of the

Melians and Athenians, and what world views and attitudes toward war and

politics, the gods and morality, do they represent?

Terms and Names

|

Herodotus

Thucydides

Croesus

Lydians

Cyrus

Persians

Solon of Athens

Apollo

Delphic Oracle

Pythia |

Peloponnesian War

Lacedaimonians (Spartans)

historia

pathei mathos

oracle

dream

prophecy

omen

realpolitik

|

Resources:

|

Tuesday, Nov. 1: Summary of

the dramas so far, with a focus on Helen and Alcestis, and how they

relate to the more serious tragedies in themes, characterization,

audience response, issues of fate, life, death, fame, love, power, and

so on. A kitchen sink kind of class. |

|

|

Thursday, Oct. 27: Reading:

Euripides, Helen

|

|

NOTE:

Meet in the regular classroom, but after the quiz, weather permitting,

we will move to the amphitheater by the pond. BRING YOUR TEXTS of

Herakles and Alkestis.

Quiz

on theatrical terms and names, and on

terms/names from Aias and Hippolytos.

Preparation for class discussion

- Since we talked very little about

Herakles last time, we will incorporate the central questions from taht

class into our discussion today.

- Herakles in Alkestis is

portrayed very differently in some ways from his portrayal in Herakles.

In what ways is he different? In what ways is he the same? How

are these two different portrayals able to represent the same character in

Greek mythology -- are they able to be resolved into a single image?

Do we in our popular culture have any figures whose portrayal varies as

much? And what does is mean in Greek drama in particular, and culture

in general, that Herakles can be portrayed in the tragic and nearly comic

models?

- Alcestis is accounted a tragedy,

but to many modern readers it is not especially tragic. What does

tragedy mean to us? And is there a definition of tragedy we can apply

to ancient Greek theater that incorporates the very different plays we have

read (including these two about Herakles)?

Preparation for class discussion

- Herakles in Alkestis is

portrayed very differently in some ways from his portrayal in Herakles.

In what ways is he different? In what ways is he the same? How

are these two different portrayals able to represent the same character in

Greek mythology -- are they able to be resolved into a single image?

Do we in our popular culture have any figures whose portrayal varies as

much? And what does is mean in Greek drama in particular, and culture

in general, that Herakles can be portrayed in the tragic and nearly comic

models?

- Alcestis is accounted a tragedy,

but to many modern readers it is not especially tragic. What does

tragedy mean to us? And is there a definition of tragedy we can apply

to ancient Greek theater that incorporates the very different plays we have

read (including these two about Herakles)?

Names

- Helen

- Menelaos

- Theano

- Egypt

|

Terms

|

Preparation for class discussion

Class Plan:

- Full-class continuation of our smaller group discussions

of The Character of Pentheus and/or The Motivation and Nature of Dionysos,

with some comment on Kadmos and Teiresias (What is Wisdom?).

- Class discussion about the issues of conflict with gods

and the affliction of madness, as outlined in the Review of Previous Plays

questions.

Review of Previous Plays:

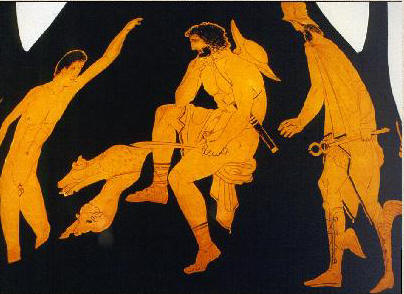

- Aias: Like Aias, Herakles is a great hero who is

brought down by madness. What are the causes of his madness?

What are the similarities between the results of the two mens' madness?

To what extent do grief and shame play a role in their resoponses when they

return to sanity? We know Aias responds with suicide -- waht is

Herakles' response to this terrible miasma? What is behind the ways in

which each man interprets his own actions and his life story?

- Conflict with a powerful and offended god plays a key role in

Hippolytos and Bacchai. NOW we see that it does so in

Herakles as well. (1) How similar are the reasons for the offense

taken by the gods? (2) What actions by the humans instigate this conflict

-- are they similar in the cases of Hippolytos, Pentheus, and Herakles -- or are there

substantial differences? To what extent does hubris play a role in these

plays?

The Character of Pentheus:

- A. Pentheus is only doing what he considers right

according to the information he has. His actions are more to protect

his city than to pursue personal glory. He may be hubristic on paper (

in that he defies a god) but he is acting in an appropriate way, and his

destruction is truly tragic -- and he is a sympathetic tragic hero --

because he is trying to do the right thing.

- Pentheus is a model of hubristic behavior in his failure

to recognize Dionysos as a god despite all the evidence of his supernatural

power. Almost all of his actions show the progression of hubris to ate

and finally to nemesis. The audience would find it hard to sympathize

with him because he is so rigid in his rejection of things he ought to

recognize.

The Motivations and Nature of Dionysos:

- Dionysos has come to Thebes from a desire to bring his

worship to his homeland and redeem his mother's name. His anger when

thwarted by Pentheus is justified, because a god with his obvious powers

should be recognized. When he appears in disguise to Pentheus, he is

essentially giving him a chance to open his eyes to Dionysos' power -- a

chance Pentheus refuses. His revenge is justified, and the audience

would recognize that this manifestation of divine power is the way the world

works and ultimately represents the way things have to be. When

Euripides makes him seem the underdog at first, he creates sympathy for the

disrespected god, and this sympathy keeps the audience with Dionysos

throughout.

- Dionysos is on a mission for revenge, and everything he

does is to make his own revenge more satisfying. He puts himself in

the position of underdog and speaks to Pentheus from that position in order

to lead him deeper into his misperceptions -- to lure him deeper into hubris

to get justification to destroy him. His control of the situation, and

his tormenting Pentheus (e.g. luring him to dress up in women's clothing)

shows him as toying with his victim in an off-putting way, and the audience

would have little sympathy for him. The audience might emerge with an

uncomfortable feeling about the relationship between gods (or at least this

god) and mortals.

What is wisdom?

- The chorus of Maenads has a deeper idea of what wisdom

truly is: to be flexible, give in to divine power, be open to the potentials

of other states of mind, be willing and able to abandon preconceptions and

limitations to embrace new (and maybe frightening) experiences, and to

submit to the overpowering power of the divine. Their wisdom enables

their survival and fulfillment, and is reflected in their closeness and

understanding of a mysterious and powerful god. Kadmos and Teiresias

represent wisdom, in which truly wise old men are able to abandon their

pride and self-image and recognize another form of wisdom. The end of

the Bacchae, in which so many meet their destruction, demonstrate the

power and validity of this kind of wisdom.

- The "wisdom" of the Maenads, Kadmos and Teiresias is a

frightening loss of self that would alienate the Greek audience (and maybe

us as well). Kadmos and Teiresias may save themselves by wearing fawn

skins and dancing around, but they make themselves ridiculous when they do

so and lose the dignity and wisdom they have earned through a lifetime of

accomplishments. The Asian Maenads are the opposite of what any Greek

(or American) would aspire to being, and their view of embracing insanity

and submitting to the divine are fundamentally alienating. The

Bakkhai leaves the audience uncomfortable because it represents a

victorious assault on their own traditional ways of understanding wisdom and

moderation.

| Names |

Terms |

- Hera

- Zeus

- Amphitryon

- Heracles

- Megara

- Lykos

- Theseus

- Iris

|

- athla (12 Labors)

- parerga (incidental deeds)

- lyssa (madness)

- tyrant

- supplication

|

Terms and Names

Names

- Pentheus

- Dionysos

- Kadmos

- Teiresias

- Agave

- Semele

- Zeus

- Apollo

|

Terms

- Maenad / Bacchante

- sophia

- sophrosyne

- Dionysiac

- Apolline

- know yourself (gnothi seauton)

- nothing in excess (meden agan)

|

|

Thursday, Oct. 13: Reading:

Euripides, Hippolytos

Artemis Power Point (from Dr D's Mythology class)

One of the Euripides resources

listed below |

|

Preparation for class discussion

- Review the ways in which Athena

interacts with Aias and Odysseus in Sophocles' Aias. In what

ways are these relationships similar to and different from the interactions

of Artemis and Aphrodite with their favored ones, Hippolytos and Phaidra?

- Hubris is a central element of Greek

drama. In what ways are the human characters of Hippolytos hubristic

(if they are)? Who is and who isn't? Who is or isn't hubristic

in Aias?

- What impression of Hippolytos do you

get, both when you first see him and in his later appearances-- is he

admirable? obnoxious? normal? obsessive? pure?

mysogynistic? Some or all of the above? Does he change in the

course of the play, or become more confirmed in his own perspectives?

Does he have a hamartia, and if so, what is it? Is he hubristic in his

rejection of Aphrodite, or is Aphrodite simply offended by his closeness to

another deity?

- What is the relationship between

Hippolytos and his father? Between him and his stepmother (before

Aphrodite's interference)? What is the relationship between Theseus

and Phaedra (to the extent you can tell)?

- From the perspective of

anthropological structuralism, what bipolar oppositions characterize the

central conflicts of this play?

|

Terms

|

Names

- Euripides

- Artemis

- Aphrodite

- Theseus

- Hippolytus

- Phaedra

|

|

|

|

Resources:

Euripides:

brief biography & commentary, informal & easy to read

Perseus entry on Euripides: A more scholarly introduction. You can

skip the section on Old Comedy and focus on the aspects of his career and

perspective.

The Fatal Hunt Part 5:

This is the Indian drama I mentioned in class Thursday that shows (in a

different medium) the impact of singing in emotionally conveying elements of the

drama. The part I mentioned starts at about 3:50, when the prince realizes

he has killed a boy. This entire drama is sung, so in that respect it is

very different from Greek drama, and it is impossible to tell how similar or

different the music would be, although it clearly isn't in any Greek meter.

I put it up for cultural comparison.

Movie: Spike Lee, Do the Right

Thing. I mention this because it has a number of elements of Greek

tragedy in a modern (well, in 1989) setting. It takes place in one day and

expresses the culimination of years of tension (racial in particular, but also

personal and pwer-based and cultural) -- just as Greek tragedy does. It

has long speeches and stychomythia, and although there aren't any choral odes,

the music makes a distinct commentary. Of course it is more visual and far

more realistic than Greek tragedy, but its narrative is not conventional and it

relates experience to the audience in different modes. Watch it if you

can. Spike Lee made this on a shoestring and it instantly made him one of

the most respected up and coming directors of his time.

Preparation for class discussion

- We will compare the ideas of shame,

anger, & warrior identity in the Iliad (Akhilleus & Hektor) and Archilochos

with that displayed by Aias in Sophocles' play. Be ready with some

comparisons and passages to look at.

- Review the Temple University study

guide and consider its questions as you read; be prepared to discuss.

|

Terms

|

Names

- Sophocles

- Aias (Ajax)

- Tekmessa

- Athena

- Odysseus

- Teukros

- Menelaos

- Agamemnon

|

|

Thursday, Sept 29: Reading:

|

|

Assignment Due: Source and Citation

Exercise

Class Preparation:

For discussion:

- The

discussion questions/class objectives are on the Pindar handout linked

above.

|

Tuesday, Sept 27: Reading:

|

|

Primary Source Readings:

Source and Citation Exercise

EXTENSINON till Thursday --

Since your example is not up, which gives you less guidance, this will be due on

Thursday instead. This is only one class before the midterm, so I will

(sigh) grade them all on Thursday night and have them ready for you by Friday at

noon (outside my office) so that you can have feedback on them you may find

helpful for the midterm.

NOTE: The example is up now on the

Important Information page.

Class Preparation:

For discussion:

Read all poems, with a couple of aims in

mind:

- Articulate the life perspective you see

in the poet's work: his/her

- day to day concerns

- ethical concerns,

- environment

- lifestyle

- relationships

- pastimes

- social status

- personal feelings

- etc.

- Choose a number of poems that stand out

to you in order to examine in more detail they way they express ideas about

the issues above or any others. Be ready to refer to these poems

specifically, or to describe the narrative strategy they use to make their

points.

- What is particularly masculine about

Archilochos, and particularly feminine about Sappho (both from our

perspective, and from the perspective that emerges in reading while

attempting to read past our own cultural constructs)?

- In what ways does Archilochos stray

from the heroic ethos of the Homeric warrior, and in what ways does he

exemplify it?

- Likewise, in what ways does Sappho

stray from the model of the good wife in Homer, and in what ways does she

exemplify it?

NOTE that while the pictures of individual

lives portrayed by Archilochos and Sappho are very distinct and engaging, they

are still writing through a persona.

Names:

- Archilochos

- Sappho

- Pindar

Terms

-

Lyric poetry:

literally, poetry performed with a lyre (so these are songs rather than

spoken poems). Lyric poetry typically expresses feelings and situations;

most lyric poems are not especially long (as they are songs).

-

Persona: The character in

which a poet writes of emotions, experiences, etc. While Archilochos

and Sappho seem to be expressing deeply personal ideas, we cannot be certain

that this is a truthful, honest portrayal of an individual, or a persona

which the poet adopts for artistic purposes (although the choice of persona

in which to write does say something about the perspective of the poet).

-

Fragments:

because of the fragility of manuscripts and the fact that most

classical literature is preserved in works copied by monks in the Middle

Ages, many lyric poets (especially the ones who deal in sexual and/or

transgressive material, like Sappho and Archilochos) were not preserved in

full manuscripts. Their poetry was preserved primarily in works that

discuss literature, in which brief quotes from the poets are excerpted for

discussion.

-

Meter:

the patterns of sounds and rhythms that characterize poetry. Lyric

poetry was written in a number of different meters (some of which were

favored and/or invented by particular poets). The meter of a poem is

important in the way in which the words and images unfold in sound and

music. This is extremely hard to reflect in English, because the meters of

our poetry are far more simple.

-

Iambic:

a meter that is often used in satyrical poetry; its rhythm was especially

well paced for straightforward, hard-hitting commentary

-

Choral ode:

A poem/song that is sung by a chorus (group of singers,

usually men), often accompanied by patterned movement in performance.

Choral odes were performed on public occasions, often at religious

festivals. Pindar’s poems are choral odes.

-

Strophe, Antistrophe, Epode:

Choral odes have a formal structure of these three parts.

Strophe means “turn” and in patterned choral movement, it is the part of the

song in which the chorus moves from right to left; antistrophe is the

left-to-right movement, and the epode is centered. The structure of the

poem in these three divisions is often used to present two contrasting or

complementary ideas/images, with the epode representing a

resolution/commentary.

-

Epinician ode:

Poems written to celebrate the victory of an athlete in the major

athletic competitions in which Greeks from many cities gathered to compete.

The games whose victors Pindar celebrates are four-yearly contests: Olympian

1 celebrates a victor in the Olympics (held at the sanctuary of Zeus at

Olympia).

-

Hoplite:

A heavy-armed soldier, with armor (breastplate, greaves, helmet) armed

with a shield, spear and sword. Soldiers provided their own weapons and

armor. In historical Greek warfare (as opposed to Homeric individual

battles) battles were fought by lines of hoplites ranged against each

other. Holding the line was essential, and the proper thing to do if you’re

losing is to retreat and reform the line. Tossing your shield (so you can

run away faster): not so good.

|

Thursday, Sept 22: Reading:

|

|

Class Preparation:

For discussion:

- Find scenes that reflect the following

motifs and suggest the reasons why this motif (narrative strategy, etc.) is

used:

- recognition (what makes it

happen, how can it be manipulated, is it a good thing, does it show

affinity, trust, chance, alliance, etc.)

- lies: Odysseus tells many lies;

what are the purposes of some of them (include some with obvious purposes

and some not so much ...)

- status: Odysseus has allies of

both high and low status -- what role does status serve in determining one's

role and value in Ithaca? Is this at all similar to the Odyssey?

- intelligence: its role in

Odysseus' wider household

- revenge: how important is it

compared to being reunited with loved ones?

- identity: in the light of his many

disguises, how does Odysseus re-establish his identity in Ithaca? How

about his family?

- Keep in mind key binary oppositions, among which are:

- male and female

- civilized and uncivilized

- strangers and colleagues

- human and animal

- conscious decision and unconscious

acquiescence

- intelligence and foolishness

- good and bad (or proper and improper)

relationships with deities

- and whatever else you notice.

Come with a few examples to draw on.

You can focus on the event's) you use for your writing assignment, but

should consider others as well.

Look over the

Returns power point (from Mythology

class) for an overview of the returns of Greek heroes from Troy and some

visuals of scenes and events from the Odyssey

Names

| Odysseus |

Telemachos |

Penelope |

| Athena |

Poseidon |

Nestor |

| Menelaus |

Helen |

Nausikaa |

| Phaiacia |

Circe |

Kalypso |

| Cyclops |

Polyphemus |

Lotus eaters |

| Laestrygonians |

Scylla |

Charibdis |

| Sirens |

Aeolus |

Helios |

| Eurykleia |

Eumaios |

Argos |

Terms

| nostos |

xenia |

xenos |

| philia |

structuralism |

binary oppositions |

| dialectical structure |

Claude Levi-Strauss |

|

-

nostos: means

"homecoming," and important concept in the Odyssey. Nostos implies

being reunited with those you love, in your native land, with normalcy

established and taking up the life you had to leave behind ...-

-

xenia:

guest-friendship, a sacred bond between visitors and their hosts. It

involves the formal exchange of gifts and a commitment to maintaining that

friendship over generations and despite conflicts (e.g. their grandfathers'

xenia was the reason Glaukos and Diomedes decided not to fight each other,

though on the opposite sides of the war; Paris violated xenia when he stole

Helen ...)

-

xenos: a guest-friend

(i.e. someone with whom this bond has been established)

-

philia (discussed

relative to the Iliad): the kind of love one can feel for family and

dear friends -- a close and meaningful emotional relationship

-

structuralism

(anthropological): a system of studying cultures that attempts to define

underlying systems of meaning that are not necessarily

understood/articulated within the culture, but that appear in myths,

literature, cultural customs and rituals, etc. It uses tools such as

dialectical structures and binary oppositions to determine the points of key

underlying tensions in the culture

-

binary oppositions: the

opposite concepts/ categories (such as male/female, nature/culture, etc.)

that reveal a culture's underlying tensions and structures (in

structuralism)

-

dialectical structure: a way

of understanding ideas and processes by looking at a value (thesis), its

opposite (antithesis) and noting the ways in which they interact and evolve

(synthesis)

-

Claude Levi-Strauss: the

founder of anthropological structuralism

|

Tuesday, Sept 20: Reading:

(it would be a good idea to read ahead in

18-24 since we will focus on that on Thursday, which doesn't leave much

time for a lot of reading)

|

|

Class Preparation:

Writing assignment due: This is a

one-page or so response that counts as a quiz grade. Topic: Choose one or

more of the "adventures" Odysseus narrates in books 8-11, and his trip to the

underworld at Circe's behest. Discuss it in terms of identity, considering

one but not necessarily all of the following issues (and/or any other

perspective you find important): how does this scene illustrate key factors of

Odysseus' identity? Does it raise questions about it, or show ambivalence,

or illustrate different features of identity from what you have observed in him

elsewhere? In what ways does it illustrate teh key characteristics of

Odysseus, adn the things he holds important? Does it reveal his identity

in terms of relationships (to enemies, allies, men, ambivalent figures?

NOTE: You should look over these questions, determine which event(s) you want to

discuss, decide which questions/approaches seem most helpful to you for your

scene(s), and begin with a thesis statement that summarizes/predicts the

perspective /conclusions you will draw.

For discussion:

- Continue to consider some of the

elements we have noted in class but not really pursues: the idea of

disguise, the different kinds of action / intelligence available to/used by

the two young people (male Telemachos, female Nuasicaa); the role of

Odysseus' elaborate stories, the relationship of Athena and Odysseus ...

- The Anthropological structuralism

summary linked under readings notes that cultures have hidden systems of

meaning that can be elucidated by observing binary oppositions. (In

the reading, you can skim the first couple of paragraphs, but note in

particular the idea of a dialectical process, binary oppositions, and the

idea of hidden systems of meaning). SO: consider the adventures of

Odysseus in terms of some key binary oppositions, among which are:

- male and female

- civilized and uncivilized

- strangers and colleagues

- human and animal

- conscious decision and unconscious

acquiescence

- intelligence and foolishness

- good and bad (or proper and improper)

relationships with deities

- and whatever else you notice.

Come with a few examples to draw on.

You can focus on the event(s) you use for your writing assignment, but

should consider others as well.

Look over the

Returns power point (from Mythology

class) for an overview of the returns of Greek heroes from Troy and some

visuals of scenes and events from the Odyssey

| Home |

Assignments |

Syllabus |

Important Information |

Internet Resources |

UNC Library |

Classical Studies |

|

Thursday, Sept 15: Reading:

- Homer, Odyssey 1-7, 14-17 (or

so)

|

|

Class Preparation:

For discussion:

- Read the opening of book 1 carefully --

focus on the portrayal of Odysseus and his story in the first lines, the

roles played by the gods in their council, and the story of Agamemnon and

Orestes. What situation(s) and themes does the opening of the Odyssey

prepare us for?

- Some central themes in the Odyssey are

family, intelligence, and homecoming. How do these themes manifest in

Telemachos' trip to see his father's friends, the role of Helen, Penelope's

situation and response to it, the relationship of Odysseus and Calypso, and

the relationship between Odysseus and Athena (and any other places you see

it)?

Look over the

Returns power point (from Mythology

class) for an overview of the returns of Greek heroes from Troy and some

visuals of scenes and events from the Odyssey

|

Tuesday, Sept 13: Reading:

|

|

Class Preparation:

For discussion:

- Look over the table of contents of

Achilles in Vietnam, and apply the topics to what you see in the

presentation of Akhilleus in the Iliad (throughout). Read

chapter 3 in depth and consider the implications of the emotional bonds

formed in warfare for the presentation of Akhilleus in particular, and the

other warriors in general. Do you see anything like this in the Trojan

warriors? In the other Greek warriors? Is it a helpful key to

understanding the portrayal of Akhilleus in the Iliad?

- Review the character of Odysseus in the

Iliad -- what are his key characteristics? In the

Trojan War power point, there

are some other aspects of his character and portrayal revealed (e.g. his

idea of the Trojan horse, his murder of Astyanax). Consider this in

the light of what you learn about Odysseus in the first lines of the

Odyssey. Is this the same character? (An idea we will return

to again.)

- In Odyssey 1-4, we are

introduced not to Odysseus, but to his son and wife and to the goddess

Athena as the helper of Odysseus and his family. How is Telemachos

portrayed? Does he exhibit any of the qualities of intelligence and

cleverness that his father does?

|

Thursday, Sept 8: Reading:

|

|

Class Preparation:

- Quiz on

terms and names linked below (with rubric).

I will give you a list of 10-12 names/ideas and you will write me a

paragraph containing at least 5 of them.

For discussion:

- Choose one or more battle scenes and

l00k at the effect of elements such as the portraits of the combattants, the

role of the gods, the interaction of the combattants, the aftermath of the

conflict, etc.

- Look for several instances of where the

gods take an interest in or directly affect the humans in the war.

What sorts of relationships between gods and humans are portrayed?

What is the range of them? What are the gods' motivations for their

actions for or against humans? Be prepared to bring up a specific

scene that illuminates these ideas (and be able to tell us where it is in

the text ...)

Reading guide:

We will focus on a few specific elements,

centered on Akhilleus:

- Beginning in book 19, Akhilleus enters

into a rather strange set of perceptions and behaviors. What are some

of the attitudes he expresses (toward the war, toward his quarrel with

Agamemnon, etc) that vary from his previous views? Why does he reject

ordinary human things (food, drink, sleep) and how is he able to do so?

What form does his mourning for Patroklos take -- what does he remember,

what does he do/not do, to what degre does his focus on revenge dominate his

consciousness?

- Early in book 21, a young son of Priam,

Lykaon, asks Akhilleus for mercy. He got it once before -- why does he

not get it now? What perspective on life & death does Akhilleus state,

and what does it mean that he has reversed his previous behavior?

- In book 21, there are a number of

conflicts in which gods and other divinities (the river) take part.

What is the significance of Akhilleus' battle with the river? How do

the gods relate to one another in the accompanying battle?

- The gods turn on and abandon Hektor in

book 22. To what extent is fate responsible, and to what extent is it

divine choice (Apollo is a good one to focus on here).

- Back to Akhilleus, who continues his

strange, dissatisfied state after he has his revenge. What

actions/expressions characterize his response? Why doesn't he bury

Patroklos? When he does, how does he act at the funeral?

- The gods finally interfere to make him

give back Hektor's body. Why? And how do Akhilleus and Priam

relate to one another when Priam comes to ransom the body?

Quiz

Terms and Names

| Greeks |

Trojans |

Gods |

Terms |

- Akhilleus (Achilles)

- Patroklos

- Briseis

- Agamemnon

- Menelaos

- Diomedes

- Aias

- Teukros

- Odysseus

- Nestor

- Myrmidons (Akhilleus' warriors)

- Akhaians = Greeks

- Danaans = Greeks

|

- Priam

- Helen

- Paris (Alexandros)

- Hector

- Andromache

- Hecuba

- Dolon

- Sarpedon (Lycian)

- Glaukos (Lycian)

|

- Zeus

- Hera

- Athena

- Apollo

- Aphrodite

- Thetis

- Poseidon

- Ares

|

- time

- geras

- aristeia

- oral poetry

- kleos (fame)

|

Rubric:

- A: a coherent paragraph showing

detailed knowledge of the terms/names chosen and interrelating them

effectively into a unified comment

- B: strong knowledge of terms chosen,

and some interrelating of the concepts

- C: Awareness of the meaning and

significance of the names and terms

- D-F unfamiliarity with names & terms

|

Tuesday, Sept 6: Reading:

|

|

Class Preparation:

For discussion:

- Choose one or more battle scenes and

l00k at the effect of elements such as the portraits of the combattants, the

role of the gods, the interaction of the combattants, the aftermath of the

conflict, etc.

- Look for several instances of where the

gods take an interest in or directly affect the humans in the war.

What sorts of relationships between gods and humans are portrayed?

What is the range of them? What are the gods' motivations for their

actions for or against humans? Be prepared to bring up a specific

scene that illuminates these ideas (and be able to tell us where it is in

the text ...)

Reading guide:

Be sure to read Book 16 thoroughly

as several key events happen there.

- Book 13: Poseidon and Zeus both take

part in guiding warriors and armies in this book. What are some of the

ways they affect, inspire, or discoursage humans? How does the

conflict of these divine brothers play out in the human world, as opposed to

in how the gods involved relate to one another?

- Book 14: What does the "beguiling of

Zeus" by Hera show about the nature of the gods in the Iliad? Does it

have any special implications about the gods' feelings toward the humans in

the battle?

- Book 15: How is Hektor portrayed in

this section where he very nearly sets fire to the Greek ships? What

images or terms or similes describe him? How do the Greek warriors

(try to) deflect his attack? And how does this portrayal of Hektor fit

in with the view of him in Book 6 (with Andromache and Astyanax)?

- Book 16: Akhilleus and Patroklos

were regarded as the model of masculine heroic friendship in the Greek

world. How is their relationship portrayed at the crucial time when

Akhilleus allows Patroklos to fight for him? Zeus allows his son

Sarpedon to be killed, despite his love for him. What relationship

between gods, fate, and men does this incident show?

- Book 17: What are the thoughts and

intentions of the men who battle over Patroklos' body?

- Book 18: How does Akhilleus respond

to the death of his friend? What is the point of the detailed

description of the shield Hephaistos makes for him>

General questions:

- What is the effect of the many

individual stories told about the otherwise unknown warriors killed by major

heroes?

- One of the best-known elements of

Homeric style is the use of similes. So what effect do they have in

the narration, and what do they add to the audience's response

to/appreciation of the scenes in which they occur?

|

Thursday, Sept 1: Reading:

|

|

Class Preparation:

Go over the discussion questions below,

and use them to guide your reading. Focus on the ones assigned to you

and be prepared to take the lead in class discussion with them.

- Book 7: The combat between

Hektor and Aias:

- What is the reason for this combat

between the two heroes? What does this say about how armies and

warriors function in the world of the Iliad?

- Describe the feeling of the combat

between the two heroes. How is each characterized?

- Why does the combat end, and what are

the attitudes of the heroes in ending it? What does this say about

their ideas about fate, the gods, adn human destiny and choices?

- What is the feeling between the

warriors and the armies at the end of the battle?

- Book 8: The gods take part in

the war:

- To what extent do the gods guide and

manipulate the human combat at this point of the war?

- What is their reason for doing so?

What is their attitude toward the humans as they insert themselves into the

battle? Give examples/ support for your answer.

- Book 9: The Embassy to

Akhilleus:

- What are the reasons Odysseus, Aias and

Phoinix give to Akhilleus for why he should come back to the battle?

How does each relate to the heroic ethos?

- What are the arguments Akhilleus gives

for not returning to battle? Is there anything confused or

contradictory in his speeches?

- Why does he refuse to return, when he

has been offered a huge geras to make up for his previous slighting by

Agamemnon?

- Book 10: Raid on the Thracian

camp

- Is there anything wrong with killing a

bunch of enemies in their sleep?

- What role does Athena play here, and

how do Diomedes and Odysseus relate to the goddess (and she to them)?

- Book 11: Battles

- pick any battle in this section and

describe the relationship between the warriors, why one wins and one loses,

divine intervention, the idea of fate, the warriors' articulations about

life, death, fate and teh gods, and anything else you feel is central to the

aprticular conflict.

- Book 12: Battle with Glaukos and

Sarpedon:

- The battle is narrated with attention

to the Greek and Trojan side alike. How does this strategy illuminate

the nature of the conflict? What is the role of the gods in this close

fighting?

| Greeks |

Trojans |

Gods |

Terms |

- Aias

- Teukros

- Odysseus

- Nestor

- Myrmidons (Akhilleus' warriors)

- Akhaians = Greeks

- Danaans = Greeks

|

- Hecuba

- Dolon (Thracian)

- Sarpedon (Lycian)

- Glaukos (Lycian)

|

- Zeus

- Hera

- Athena

- Apollo

- Aphrodite

- Thetis

- Poseidon

|

- time

- geras

- aristeia

- oral poetry

|

-

time: honor, gained by heroic deeds and awarded by one's peers

-

geras: a gift of the spoils of war, allotted by one's peers, that is the

visible manifestation of time

-

aristeia: a narrative in which a particular warrior gets ready for battle

and shows his excellence by defeating all opponents

-

oral poetry: poetry that is not written but kept alive in an oral tradition.

Oral poetry has been studied in many forms in 20th century non-literate

peoples. Some oral poetry is set and unchanging, but most is

flexible, changed by the poet/singer depending on audience, circumstances,

etc. "Homer" may be a traditional name for the poet of the Iliad and

Odyssey, while the poems arise primarily from a shared oral tradition.

Tuesday, Aug. 30:

Reading:

Class Preparation:

- Read the Syllabus and come to me with

any questions.

- Be prepared to lead/respond to the

discussion questions.

In class we divided these up so that you would be ready to contribute

to/lead other students in discussion of the questions assigned to you.

But everyone should be ready with comments on all topics. Use the

questions to guide your reading.

- Review the

Trojan War Power Point (from my

Mythology class) to get an idea of the whole myth, the lead up to and

aftermath of the Iliad, and get a sense of the visual representation of the

heroes and events. Also, there is a good summary of the heroic ethos

(esp. time and geras).

- Go over the second curse tablet and

determine: who is doing the cursing? For what reason? What

actions (of any) does s/he do to accomplish his/her goal? What exactly

does s/he want the assisting daimons to do? And what relationship of

divine and human does this curse tablet suggest?

Terms and Names

| Greeks |

Trojans |

Gods |

Terms |

- Akhilleus (Achilles)

- Patroklos

- Briseis

- Agamemnon

- Menelaos

- Diomedes

|

- Priam

- Helen

- Paris (Alexandros)

- Hector

- Andromache

|

- Zeus

- Hera

- Athena

- Apollo

- Aphrodite

|

|

Helpful resources:

Sparknotes: (I am not opposed

to using summaries like this to guide your reading, but do not limit your own

analyses to what you find in their brief discussions.)

Iliad Notes: This

site has good sections on the heroic ethos and oral poetry.

Reed

University Iliad Site: The sire has a good timeline of the Greek world, a

map of the key locations in the Iliad/Trojan war, and links to other helpful

resources, among other things.

A

Brief Introduction to Greek Gods: This is a little simplistic, but good for

situating yourself if you don't have much (or any) grounding in Greek myth.

Theoi.com:

For a much more detailed and insightful introduction to Greek gods, with a great

many primary sources as well.